New face on campus

Six objects, one story: get to know Vice-Chancellor Professor Phil Taylor through his personal treasures.

Professor Phil Taylor – an internationally leading academic researcher and industry expert in renewable energy systems – is Bath’s new Vice-Chancellor and President.

Before joining us last summer, Phil had worked in industry and academia for more than 30 years. Among his many accomplishments, he designed the grid connection for the UK’s first offshore wind farm and even oversaw a £250 million project to build the UK’s most powerful AI supercomputer.

To get to know him better, we asked Phil to select six objects that meant something to him.

Phil as a baby in Italy

Phil as a baby in Italy

A replica 12th-century Lewis chess piece

A replica 12th-century Lewis chess piece

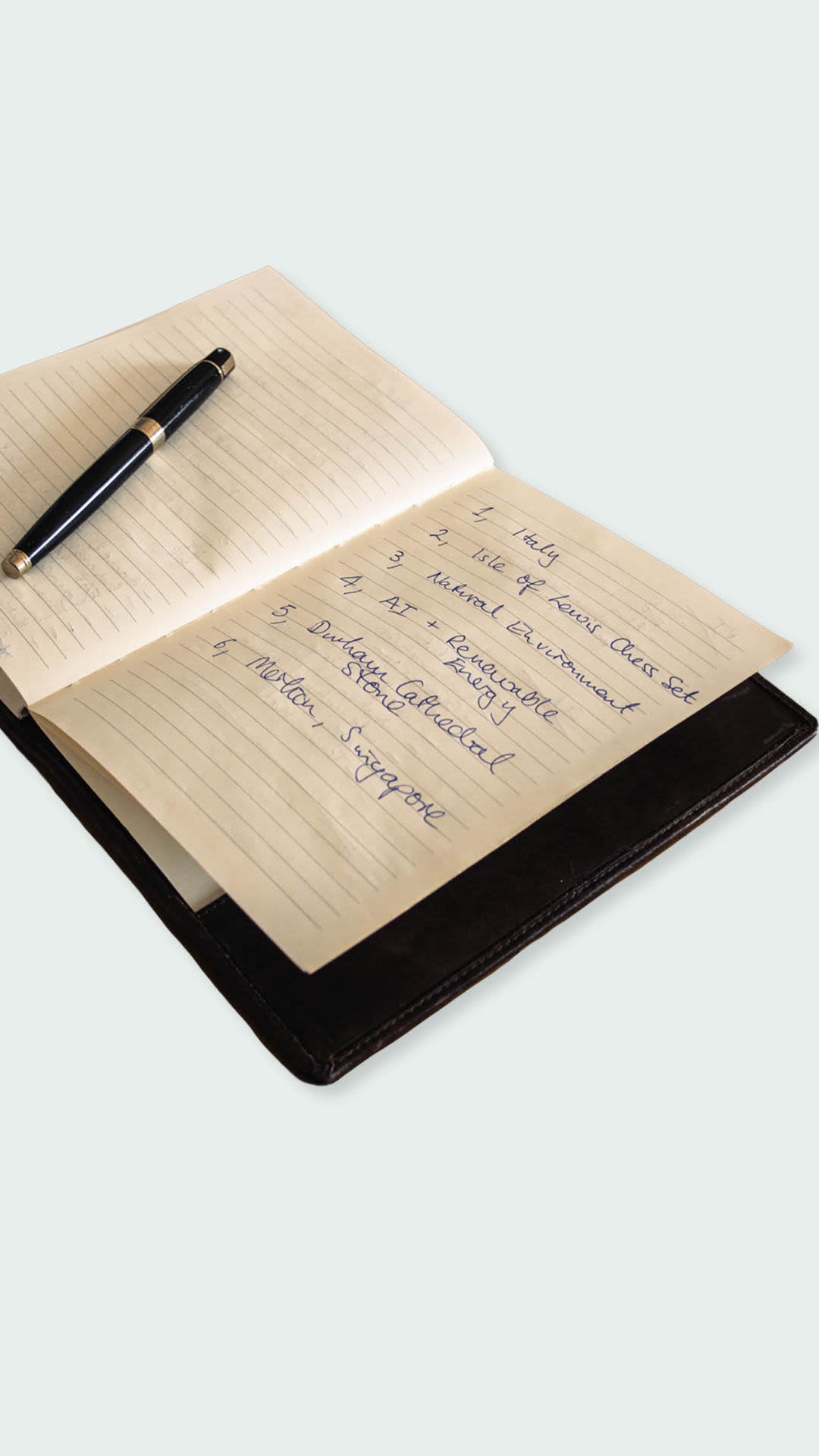

Phil carries a notebook everywhere

Phil carries a notebook everywhere

Nuclear family

I was born in Italy because my dad worked for the European Space Research Organisation. He was doing the thermal calculations for tiles on rockets, ensuring they didn’t degrade when they came in and out of the atmosphere. We lived in a little village called Grottaferrata next to Frascati – you might know it for the nice white wine – where we stayed until I was two.

My parents are British and met in the 1960s while working on fusion research at Harwell Laboratories. My mum was one of the few female scientists there at the time. They taught me a lot about nature, and how to think like a scientist. They encouraged us to question everything – to look for evidence rather than make assumptions.

A formative moment was a family trip to the Centre for Alternative Technology in North Wales. It’s an outdoor museum that demonstrates all sorts of sustainable technologies. You could pump water up a hill and see a wind turbine light up a bulb. I remember being surrounded by nature, looking at renewable energy technology, and thinking: ‘Wow, these two things go together perfectly.’ I never looked back after that.

Working in renewable energy as an engineer appealed to both my love of technology – designing things and solving problems – and my love of nature. It’s all about protecting the environment and tackling climate change.

I’m proud of Bath’s strong focus on sustainability – it’s central to our teaching and research. We were the first UK university to offer carbon literacy training to new students and have introduced a master’s in decarbonisation. We have ambitions to do even more, and partnerships and philanthropic support will be essential to creating a lasting impact.

Staying one move ahead

This is a replica a 12th-century Lewis chess piece. The real ones were made from walrus tusks and were found in 1821, buried on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland. Most of them are in the British Museum and they’re amazing pieces.

I loved chess as a kid and played in a club in Middlesbrough, Teesside, where I was brought up. It taught me how to plan and strategise, to think several moves ahead, and consider different branches of opportunity. My dad taught me how to play and would never let me win, so when I did eventually beat him, I knew I’d earned it. He’s 86 now and we still play.

Chess also trained me to focus. As a child, I didn't like sitting still. I was too energetic and easily distracted, but chess was the one thing that would captivate me enough that I would stop and concentrate. I’m still a bit like that now; it’s helpful in my job where I’ve got to multitask and do a million and one things every day.

Nota bene

Like most Bath students, I did a placement year in industry as part of my undergraduate engineering degree in Liverpool.

The company, GEC, instilled in us the importance of having an engineer's notebook or a design book. We carried them everywhere and recorded decisions, calculations and progress. When I was young, if I turned up for a meeting with my boss without a notebook, they would cancel it.

Since then, I’ve used a notebook for everything, whether I’m working in industry or academia. I’ve got hundreds of them, going back to when I was 20 years old.

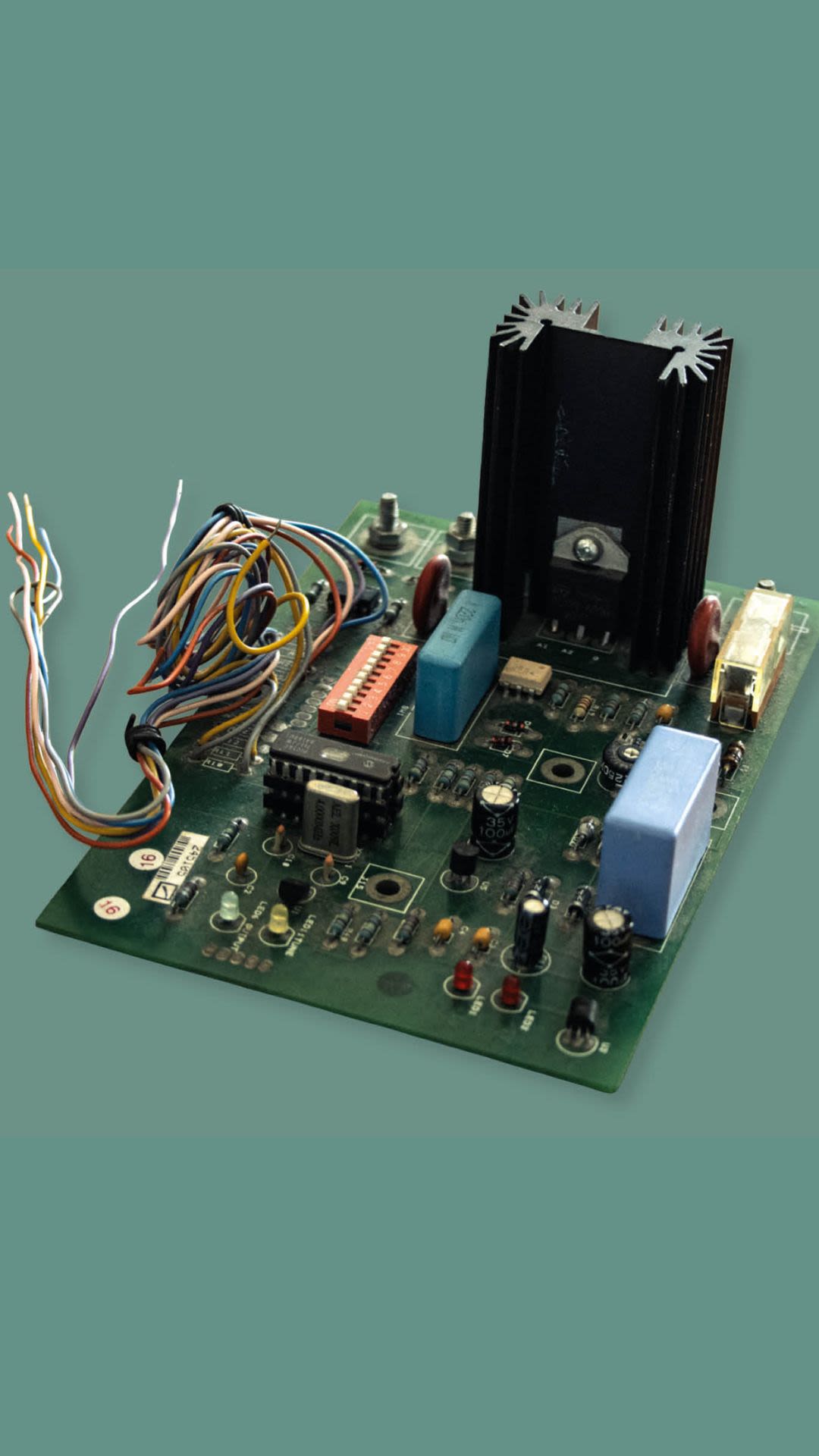

Sustainable AI

This is a prototype device that I designed for my PhD in Manchester. It was 1997 and, believe it or not, this is an artificial intelligence (AI) device for renewable energy systems.

The AI software is embedded in the chip and the rest is the electrical control system. It was sold worldwide by Econnect, the company that sponsored my PhD. It controls renewable energy systems in remote parts of the world, such as an AIDS and leprosy hospital in Uganda. The power would trip often and they would have to heat hot water bottles on a fire to keep the babies warm. I’m proud to say these devices distributed around the system reduced the power cuts from, say, 50 a month, to almost zero.

It allows you to run an energy system on 100% renewable energy by using an AI technique called fuzzy logic. If you think of Boolean logic as ‘true’ or ‘false’, fuzzy logic allows you to have an overlap. There’s ambiguity and uncertainty. You can embed that into the reasoning of the software, so it thinks like a human being. It’s also self-learning, changing its settings in pursuit of better performance.

Renewable energy and AI have been a thread throughout my career. Before joining Bath, I oversaw the project to build the UK’s fastest AI supercomputer, Isambard-AI, while I was Pro-Vice-Chancellor for Research at the University of Bristol. I also lead the Supergen Energy Networks Hub and I'm an independent adviser on the UK Government’s Net Zero Innovation Board.

I’m impressed with the AI and augmented human research here at Bath, especially the push for ethical and sustainable AI. There are big things ahead.

The Merlion’s meaning

I have a miniature of the Merlion statue situated in Singapore’s Marina Bay. I travelled there a lot, working for the Singapore government to help them make decisions about funding for energy research projects.

Then I became a visiting professor at Nanyang Technological University in their renewable energy group ERI@N. I worked with them for ten years on collaborative research and helped to grow their research programmes. They’re currently ranked 15th in the QS World University Rankings. Recently I’ve been asked to work for the Singapore government on the Scientific Advisory Board for the National Research Foundation’s CREATE Centre, which is an international research campus and innovation hub.

Since becoming Vice-Chancellor, I’ve enjoyed meeting members of our community, locally and internationally, and hearing their fond memories of the University.

Bath alumni are incredibly accomplished people, shaped by shared experiences.

I look forward to engaging with more alumni at every stage of their journey, as they continue to make an impact worldwide through their advocacy and support.

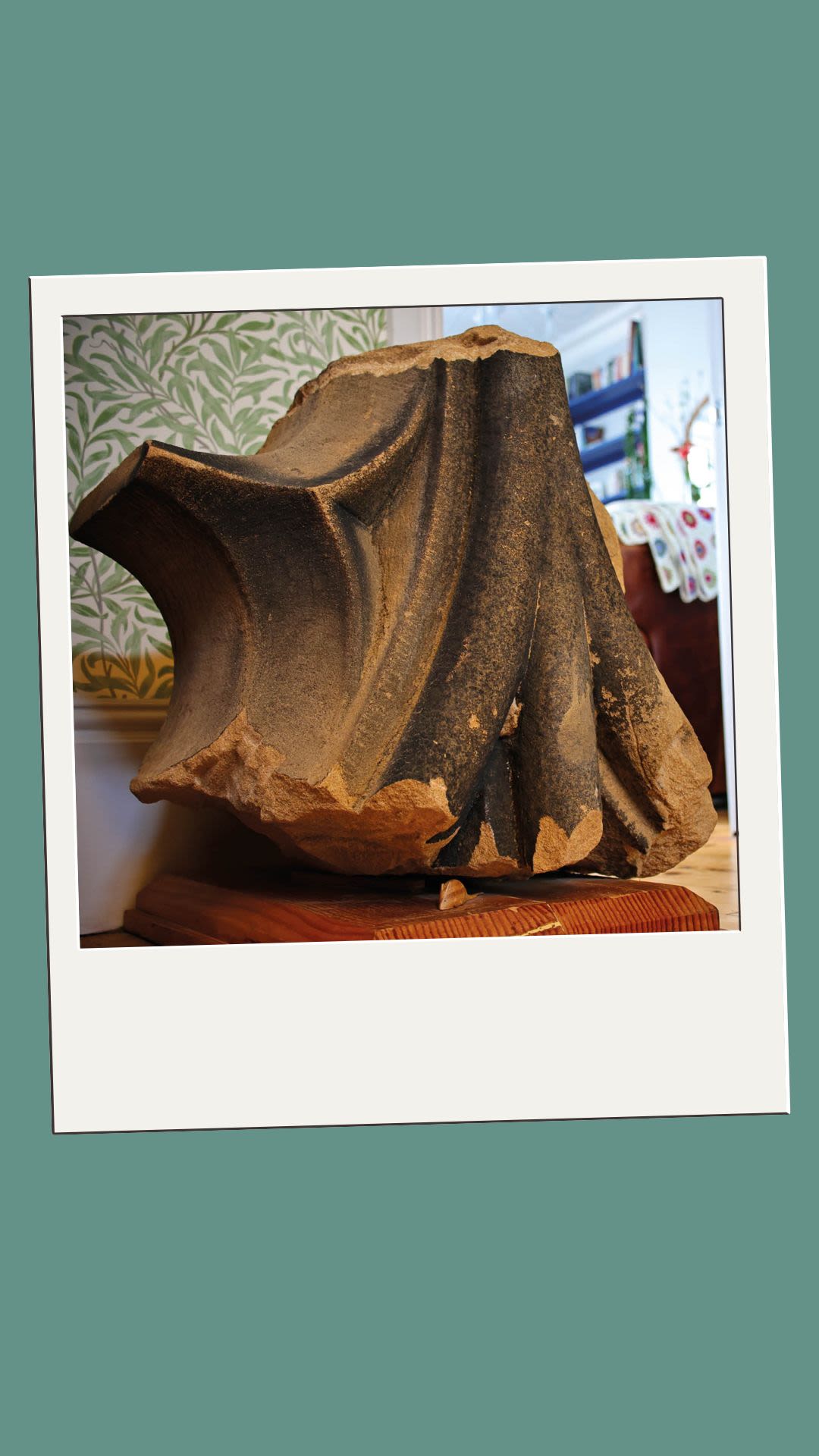

Solid foundations

Occasionally, large parts of stone from Durham Cathedral are taken down as part of the repairs and maintenance. They held an auction for charity and I managed to get this piece from the central tower. It’s enormous and I have it upside down in my hall.

Why is it important? The first academic job I ever had was at Durham University. I had resigned from my role as a research and development director to become a lecturer, having only one publication to my name. I wanted to do more radical research than I could in industry and learn how to teach. Four years later, I became a professor. Durham is also special because opposite the Cathedral is Durham Castle, which is where I got married to my wife Susie.

This stone marks an important moment in my journey and reminds me of the value of long-term thinking. Cathedrals aren’t built overnight; they need vision, patience and solid groundwork. That’s how I see my work, too – not just about the quick wins but part of a bigger picture.

With the University’s 60th anniversary coming up, I’m focused on building strong foundations for lasting success.

A prototype device Phil designed for his PhD in 1997

A prototype device Phil designed for his PhD in 1997

A miniature of the Merlion statue from Singapore’s Marina Bay

A miniature of the Merlion statue from Singapore’s Marina Bay

A piece of stone from Durham Cathedral's central tower

A piece of stone from Durham Cathedral's central tower