Surviving the extremes

Facing climate change head-on not only means working to prevent it, but to better prepare for the extreme ways it's already reshaping our lives. Discover how Bath researchers are equipping us for what lies ahead.

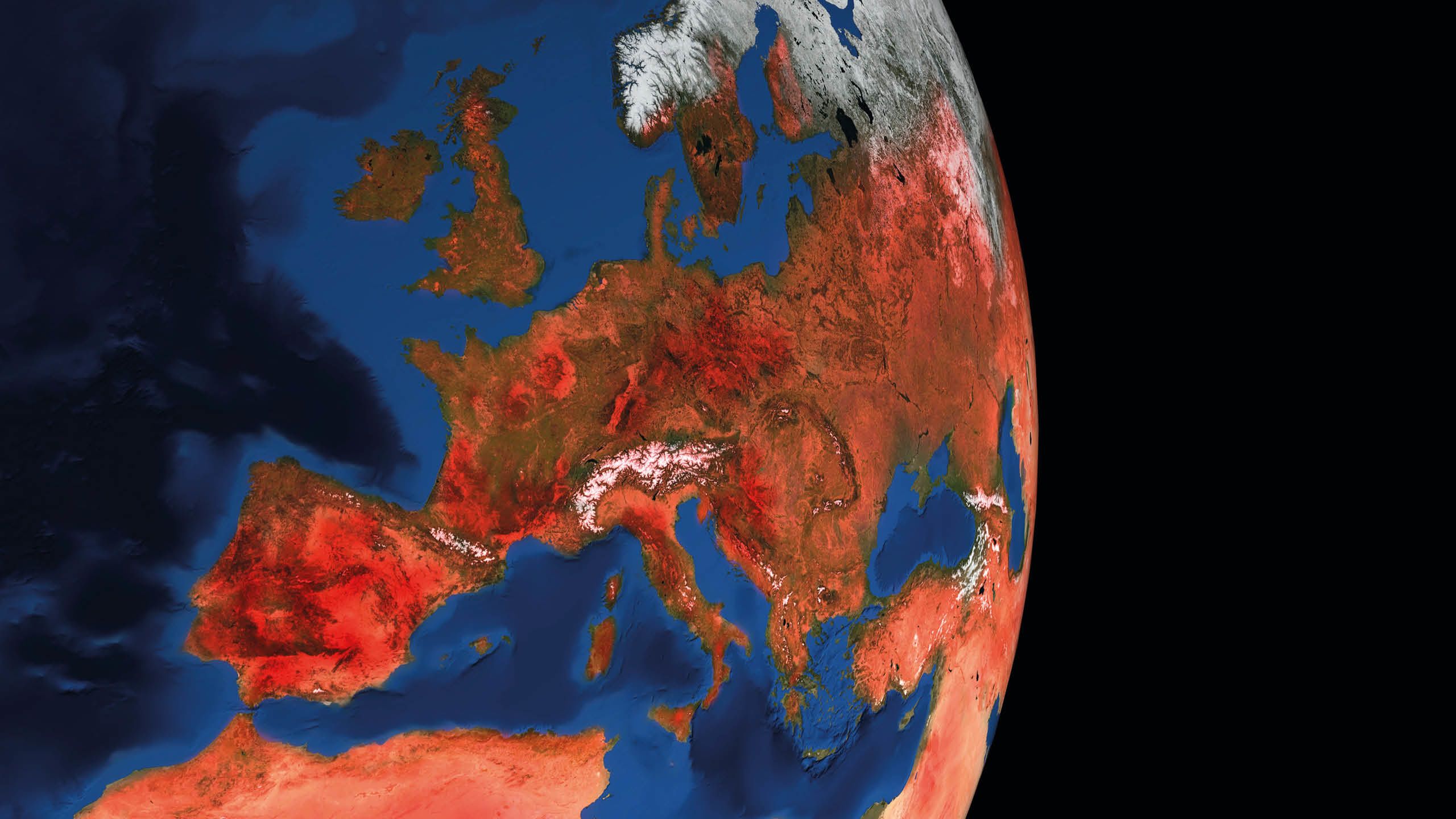

In 2003, Europe experienced a summer heatwave that caused an estimated 70,000 deaths. Crops failed, forest fires burned and people across the continent faced heat strokes, dehydration and air pollution. Heatwaves have increasingly become a frequent part of the news cycle – along with other extreme weather events including heavy flooding, droughts and storms.

As more communities are impacted and lives upturned, the urgency to better prepare for our rapidly changing climate is becoming clearer by the second. Armed with this awareness, researchers across the University are developing critical tools that will improve decision-making and help the world create the best protective strategies and infrastructure to withstand the extremes.

The 100-year event

“When engineers set out to design a flood defence, they must ask themselves ‘how high is this wall going to be?’” says Dr Thomas Kjeldsen from our Department of Architecture & Civil Engineering. “What determines the height of the wall is that it should be able to withstand a 100-year event: a flood of such magnitude that is expected to occur only once every 100 years.”

Establishing exactly what this fateful event will look like is Thomas’ specialty. He does so by looking back at past floods and running advanced statistical analysis of the data to predict what might occur in the future. The goal is to provide decision-makers, such as environment agencies, with the information they need to plan and build effective infrastructure.

It sounds entirely logical, but it comes with challenges. “The issue is that no amount of information on the past can really tell you whether something is going to behave the same in the next 50 years,” he tells us. “But this is particularly difficult today when the climate is changing so drastically.”

Rising to the challenge, Thomas and a team of engineers and computer scientists at Bath and Turkey’s Erzurum Technical University, are developing a new dynamic flooding model – but this time, using the power and potential of artificial intelligence (AI).

This advanced model will replace outdated calculations and will be trialled in Turkey due to the growing severity of floods in the country. “When in the past we never had enough global weather data, we now have so much that we’re not always entirely sure what to do with it,” says Thomas. “Machine learning is an exciting opportunity to develop new tools to take advantage of the deluge of data that’s become available to us.”

With the ability to process vast historical records of rainfall from around the country, the model can better determine the drivers of extremes. It uses information such as where the rainfall events came from, as opposed to simply how much rainfall was seen.

“The hope is that we can tell what kind of changes we might expect to the 100-year flood under climate change,” he explains. “Ultimately, the end users of our research are people like the environment agency. They have to make tough decisions; they are accountable for communities who could be flooded if they get it wrong.”

Thomas is also using AI to train CCTV systems to spot blockages in urban waterways and reduce flooding. This allows councils to make better use of resources and act in a preventative, rather than reactive, manner. It’s already attracting attention from flood prevention organisations in countries including South Africa. He adds:

“This study is a first step toward a sustainable solution to food forecasting.”

By providing critical information to decision-makers, these innovative projects are setting us on the right path to ensuring we’re better prepared for the extremes to come.me.

“Not enough people are making noises considering the scale of the likely events we will suffer”

Feeling the heat

Joining Thomas in the fight to create a more prepared and adapted world is David Coley, professor of low-carbon design. He focusses on developing buildings that keep people safe and comfortable as the climate warms.

“They’re not taking it seriously at all,” he says, when asked about the willingness of policymakers to prepare for extreme temperatures. “Not enough people are making noises considering the scale of the likely events we will suffer.”

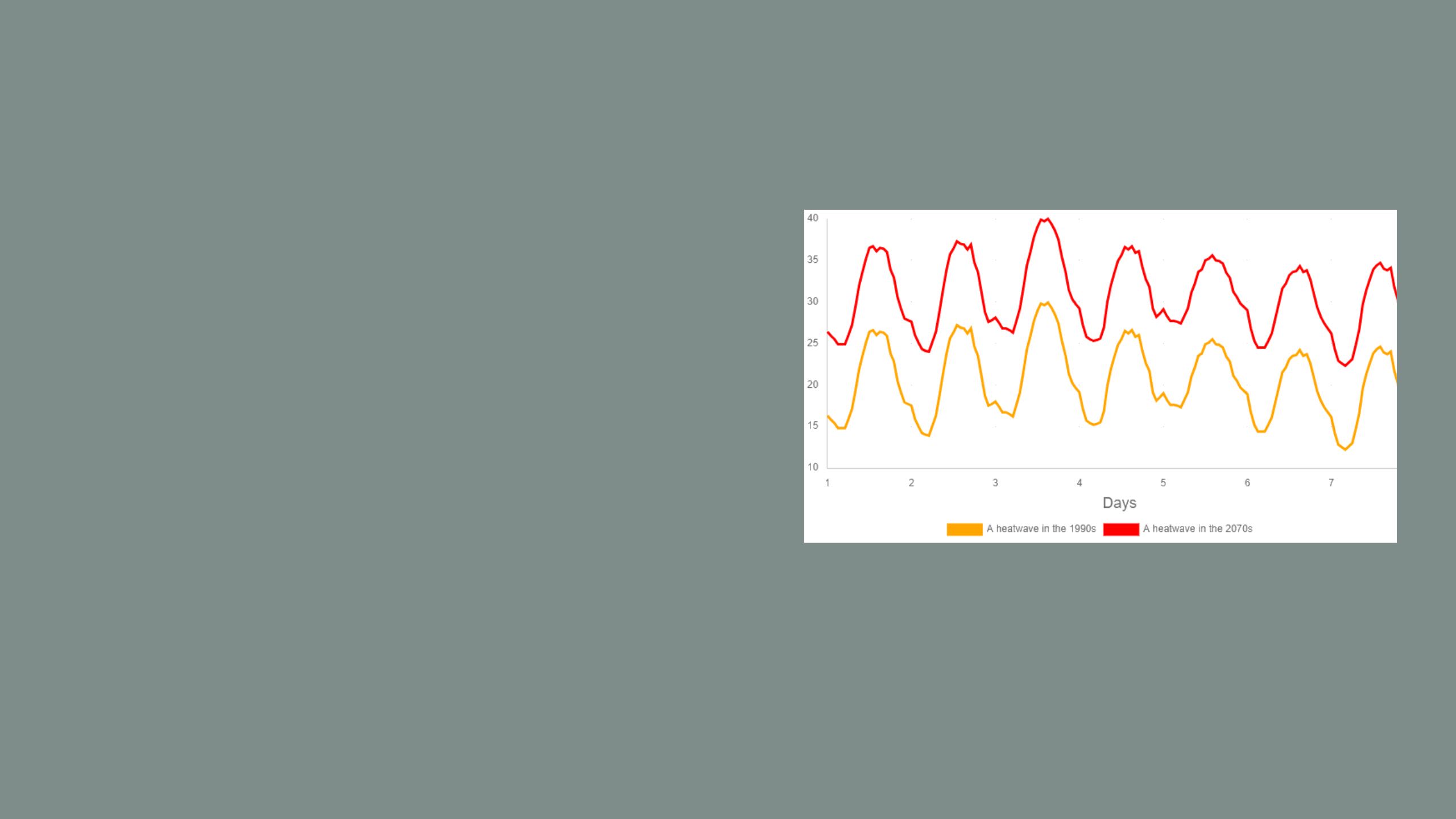

To shine a light on the severity of these events, David and a team of researchers developed a website: 'The creation of localised current and future weather for the built environment' (COLBE). Users can search from 11,000 UK postcodes to find out what an extreme hot spell will feel like in the 2070s.

“People will be surprised,” David tells us. “This is because normally climate change is discussed in terms of changes in average temperature, which is predicted to be around 2°C. Whereas the increase during heatwaves will be much, much larger.”

The site hosts a terabyte of future weather data which, with years of mathematics and coding, predicts future weather on a localised scale.

“We hope the COLBE project is the start of a discussion between the public and policymakers, with professionals using the weather files to test drive their buildings into the future,” he explains.

“We need to be very concerned about events such as the 2003 heatwave.14,000 (mainly elderly) people died in France, and almost all inside buildings that could not maintain survivable temperatures. The UK will have a similar heatwave soon,” he warns.

Since its development, COLBE has expanded to India via the ZED-i project, becoming the largest database of free weather data for the country. “The mortality and morbidity risks from climate change are of a different scale in India than Europe,” explains Professor Sukumār Natarājan, who’s leading this expansion. “The tropical climate, lower GDP and unprepared construction sector make our work even more paramount here, and other developing countries, as the risk of extreme weather increases.”

“We call this psychological distance: the sense that people elsewhere are going to be more impacted than us”

Changing mindsets

While there is a strong acknowledgement for the need to slow the progression of climate change, can the same be said about the need to prepare for the rapidly changing world we’re facing? Do policymakers and the public have the same sense of urgency?

As an environmental psychologist and deputy director of the Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations, Dr Christina Demski explores the public’s perception and experiences of the risks and impacts. Her recent work, as part of the Flex-Cool-Store project, investigated public behaviour in the face of extreme heat events in the UK – specifically the 2022 summer heatwave in Europe.

“Research shows that our perception of heat here is generally positive,” she tells us. “If you look at visuals used in the media, they tend to be of people enjoying the sun and eating ice creams.

“What we’ve found is that people are underprepared as they don’t think of extreme heat as a risk to them – or at least believe it's only for a short time so we don’t have to worry about it. We call this psychological distance: the general sense that other people elsewhere are going to be more impacted than us.”

However, if recent events are anything to go by, the UK is set for more extremes like this. According to Christina, there are signs that those in power are working to prepare communities for what’s to come; just this last year the Met Office issued the first red warning for exceptional heat. But she’s also wary that there are still significant gaps.

“We need a more joined up approach to adaptation that also connects to mitigation,” she concludes. “There's a lot of focus on retrofitting homes from a climate mitigation and health perspective, such as improving energy efficiency. But if that’s done in a way without thinking about future overheating risks, you have all these homes that won't protect communities in the long-term.”

Credit: Ornella Cacace

Credit: Ornella Cacace

Snow queen

Bath alumna Amy Macfarlane is no stranger to a cold climate. “It comes with the job description,” she tells us. “But I find it really exciting.”

Spending months at a time in the polar regions, her mission is to understand the complex factors that influence our warming planet. Her research focus? Snow, specifically on sea ice.

“We get a lot of energy transfer from the ocean to the atmosphere and the snow layer on sea ice is influencing this,” she explains. “We need to improve our understanding of snow microstructure, in particular how the snow conducts heat and reflects sunlight, to really understand how our world, and the Arctic, is heating up.”

Having studied physics at Bath, Amy went on to explore her interests further. Her PhD, which investigated the microstructure of snow in the Arctic for an entire year, won the 2024 Prix de Quervain award – honouring students and early-career scientists for outstanding research.

Among other discoveries, Amy showed that the current large-scale climate models may overestimate the thermal conductivity of snow, helping to increase the accuracy of future climate change predictions.

Today, not only is Amy working to develop the Responsible Science Initiative (RISE), which aims to reduce the environmental impact of scientific activities, but she’s also conducting postdoctoral research investigating how microwave satellite signals interact with snow.

“We have satellites passing overhead that monitor how thick the snow and sea ice is, but sometimes the snow interferes and complicates the detection of the snow-ice interface,” she tells us. “I'm trying to understand how the variations in snow structure impacts how the signal is altered.

“The bigger picture is that once we understand how the snow is influencing the signal, we can properly determine how thick the sea ice is underneath and how rapidly the climate is warming.”