Culturing meat for sustainable nutrition

Growing meat instead of rearing animals to eat could radically change our diets. At Bath, we're leading on making it work at scale.

The cost of meat

Next time you tuck into a juicy burger consider this: more than three quarters of the world’s agricultural land is used for livestock, to produce just 18% of the calories we consume globally.

What’s more it takes 163m2 of land, 728 litres of freshwater and 50kg of greenhouse gas emissions - carbon dioxide and the potent greenhouse gas methane - to create just 100g of beef protein. But what if you could eat meat without using all that land, water and other resources, while emitting a fraction of those greenhouse gases?

What if we could enjoy the taste and nutrition of meat without subjecting animals to intensive farming and slaughter while creating sustainable, ethically produced food for everyone?

That’s the vision of a team of scientists and engineers at the University of Bath working to scale up the production of ‘cultured’ meat.

Sometimes called cultivated meat, cultured meat is animal protein grown in vessels called bioreactors. Billions upon billions of animal cells are grown and then harvested as meat. And it could radically change our diets in the coming years.

Professor Marianne Ellis is the lead researcher working on cultured meat at Bath. A tissue engineer by training, Prof Ellis was initially interested in using chemical engineering to grow human cells and organs in laboratories for medical research and applications, until two chance encounters changed the course of her research forever.

Firstly she happened to bump into alternative protein pioneer Dr Hanna Tuomisto at a conference in Vienna in 2012.

“I hadn't even heard of cultured meat, and actually thought it was quite weird. But it was interesting,” says Prof Ellis. As they discussed the concept, she realised her chemical engineering expertise could be valuable.

“Hanna was explaining that they didn't have good details on the bioreactor energy requirements and materials requirements and, although this wasn’t the central application for my work, it's what chemical engineers do.

“And so I said ‘I'll give you a bit of a hand, I can look at this,’ and I started thinking that actually this is really cool, I can see huge opportunity in providing alternative proteins from the sustainability aspect.”

The large majority of our greenhouse gas emissions globally come from eating, heating and transport. Of our eating emissions, meat is a big culprit – responsible for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gas emissions from food production globally.

Meat production from ruminant animals in particular – mostly cattle and sheep – is also responsible for large amounts of methane emissions. Called a super greenhouse gas, methane traps heat in our atmosphere 84 times more efficiently than carbon dioxide (over 20 years), but persists in the atmosphere for a far shorter time.

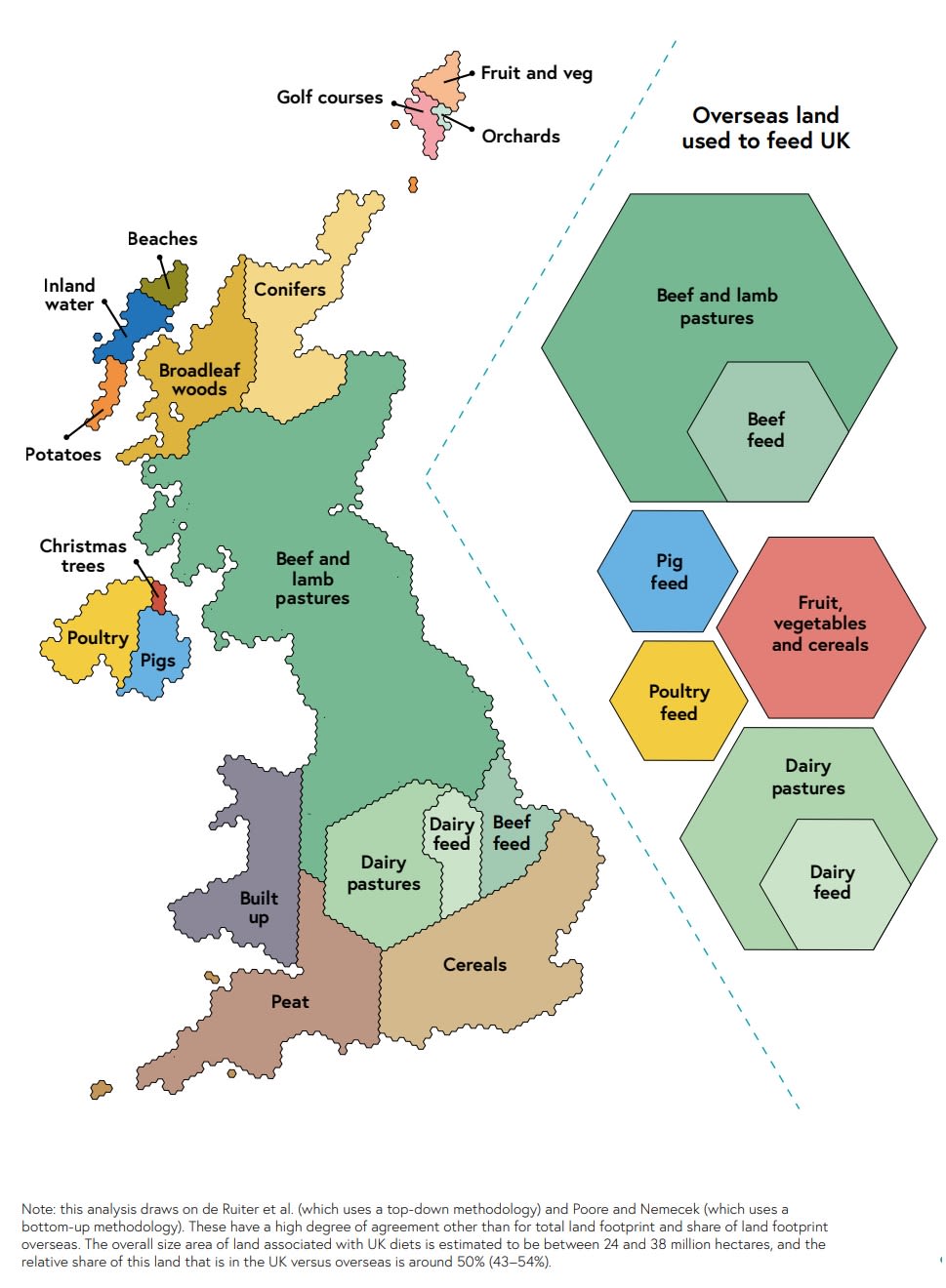

What’s more rearing animals for meat uses huge amounts of land, not only in terms of pasture for the herds to graze, but also for growing the crops that are used as animal feed.

Figure from The National Food Strategy: The Plan - July 2021

Figure from The National Food Strategy: The Plan - July 2021

In fact, the amount of land used just for rearing beef and lamb for UK consumption is bigger than the entire UK itself.

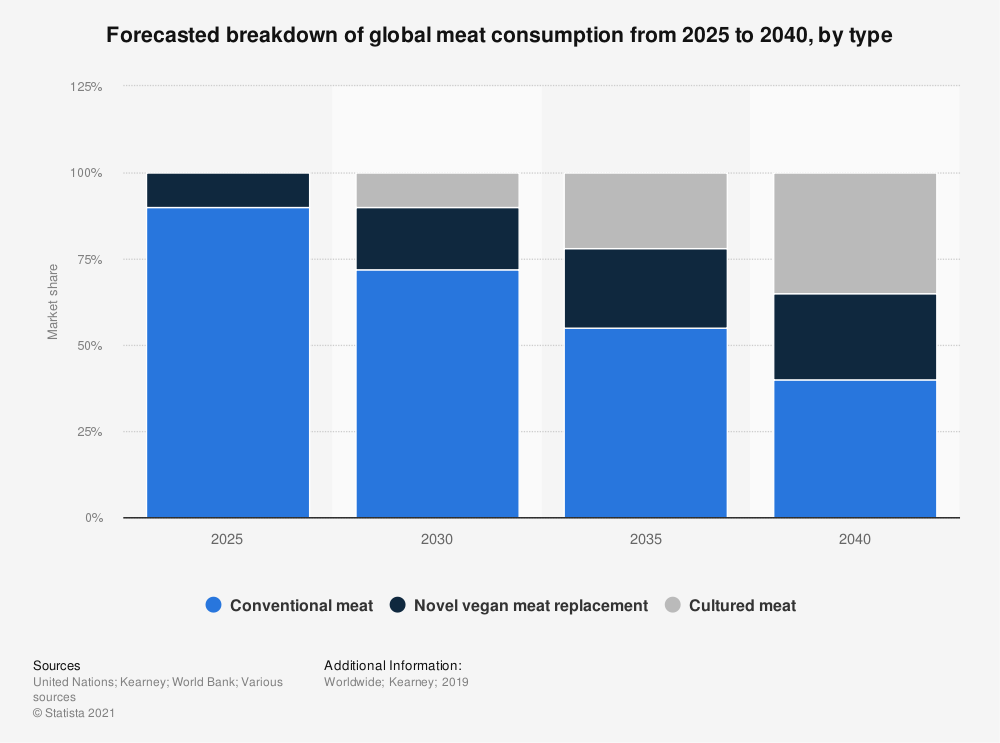

As global meat demand is set to grow it’s clear that our farming practises will need to change if we’re going to feed everyone and tackle the climate and biodiversity emergencies facing the world.

Cultured meat grown at scale could address many of these challenges, freeing up land, feed and water from use in livestock agriculture, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions all while providing nutritious, tasty protein for our diets. Meat cells could be grown efficiently, with inputs carefully measured to avoid waste and, if the process is powered by renewable energy, at very low carbon intensity, with fewer animals kept in better conditions.

Scale is the challenge

After meeting Hanna, Prof Ellis began exploring cultured meat, starting with small student projects and getting more and more intrigued. In 2015 she attended the first international symposium on cultured meat, hosted by Professor Mark Post, who in 2013 famously produced the world’s first lab-grown burger at a reported cost of $250,000.

It was there in Maastricht where Prof Ellis met Illtud Dunsford, a farmer, food consultant and food product developer who at the time was getting curious about the potential for cultured meat.

“It was very small, maybe 30 or 40 people maximum,” says Prof Ellis. “So you end up talking to everybody. I got talking to Illtud and we got on really well and got to the point where we said: ‘Oh, it'd be really cool to grow your pig muscle cells in our bioreactors.’”

Illtud Dunsford

Illtud Dunsford

Dunsford's family has owned their mixed farm in Wales for generations. At the time of the conference he had been awarded a Nuffield Farming Trust Scholarship and had been interested in the concept of cultured meat since seeing Prof Post’s lab grown burger demonstration in 2013.

It became immediately clear to both Prof Ellis and Dunsford that their respective expertise could complement each other’s work, and they began working together straight away. They then set up Cellular Agriculture Ltd in early 2016, with a mission to tackle the challenge of scaling up culturing meat.

Growing mammalian cells in a lab is actually fairly straightforward. Techniques have been well established for decades, with applications in medicine and science ranging from diagnostics and treatments to experimental research. But normally researchers want to grow as few cells as possible to keep time and costs down, producing microgrammes or even less, in cells by weight.

Cultured meat is the opposite. Eventually, if it’s going to have any significant impact on our diets then we’ll need to grow tonnes, at an affordable cost.

“Scale is a common problem for the cultured meat industry” says Prof Ellis. “Growing muscle cells on a small scale is actually not hard, we know how to do it and it’s basic in that sense. But there's a lot of optimisation that needs to be done both in terms of resources, and cost, and new, innovative technologies to do this at the scales required.

“There are companies that have set up and are manufacturing now, using technology directly from the pharma industry. Huge tanks, that are not very space efficient, not massively energy efficient, but that's fine for now, you’ve got to start somewhere.

“But what we're looking to do is to introduce technologies that allow for culturing meat in a much smaller space. Meaning higher cell densities, lower material requirements, lower energy requirements, to actually make it more affordable, and more practical to have in more places.”

In their quest to crack the scalability required to make cultured meat genuinely transformative, Prof Ellis and her team are looking at every aspect of the process, from the design of the equipment used, to the feedstuff, to the growth media, to the post-processing of the cultured muscle cells.

The team believes by optimising each step they could realistically achieve cell densities 1,000 to 2,000 times higher than culture flask and plate-based systems.

“Having this process where we can manufacture the kind of consistent good quality muscle cells that can be used in in products, and being able to offer to the industry tried and tested process for making muscle cells, that’s the goal,” says Prof Ellis.

Will people eat it?

But what’s the point going to these lengths to produce cultured meat, if consumers aren’t prepared to eat it?

Fortunately interest in cultured meat seems pretty high with around half of European consumers, two thirds of American, and an even higher proportion of Indian and Chinese consumers saying they are prepared to try it.

Dr Chris Bryant, an honorary fellow at the University of Bath who researches attitudes to cultured meat, tells me that: “Cultivated meat producers have cause to be cautiously optimistic about consumer attitudes. A recent Food Standards Agency survey found that about one in three Brits said they would eat cultivated meat, which represents an increase compared to previous surveys.

"It’s likely that cultivated meat will be viewed as more acceptable the more familiar it becomes to consumers.”

Prof Ellis also points to the fact that she sees more and more researchers, companies and finance coming into the fledgling cultured meat industry, anticipating a commercial opportunity.

Indeed by some projections cultured meat will make up to 35% of the global meat market by 2040 – representing around $630B in value.

And the size of that market addresses another common question about cultured meat – why bother when people could simply go vegetarian or vegan instead?

“At the moment the vast majority of people do eat meat, and so to give them a satisfying alternative that is more sustainable, and doesn't add pressure in terms of animal welfare, actually is something that I think can't be underestimated because meat is a key component of diets in many cultures,” says Prof Ellis.

“From a diversity perspective - both in terms of the environment and biodiversity, and for choice - it’s good to have a wide range of options – to sometimes have vegan, vegetarian or meat, and I would put myself in that bracket. I like that range so I can choose based on ethical sourcing and nutrition profile. There’s a lot of plant-based protein alternatives now, and some very good tasting products. So I think their growth in popularity would suggest that there's space for other protein alternatives, like cultured meat.

“It's not as simple, I think, as expecting everybody to go to vegetarian and vegan diets.

“Then there's another argument as well, which is about protein density. Bioavailability and digestibility is high for meat and that is important.”

A threat to farming?

At this point you might be thinking that cultured meat spells the end of traditional farming for meat, but that’s not how Prof Ellis and Dunsford see it. They envision the cultured meat industry complementing a more financially and environmentally sustainable livestock industry which gives farmers more value per animal.

The hope is that by using cells from animals to grow cultured meat, many farmers could choose to move away from intensive farming to smaller holdings with higher animal welfare standards. Their animals could instead be used to produce smaller quantities of high-end meat – particularly cuts like steak which have a texture that is technically challenging to grow using current cell culture techniques. Cultured meat grown by taking cells from herds could then be used to supply the large quantities of meat needed for everyday foods like mince.

Neither Prof Ellis or Dunsford see cultured meat completely displacing livestock agriculture – and indeed wouldn’t want to see it imposed upon societies or communities.

“I have to admit, it took some months for me to understand and accept the idea of cultured meat,” says Dunsford. “It took time for me to understand what the technology could represent, both as a threat and as an opportunity to traditional agriculture.

“As a farmer, I was very much a supporter of regenerative practice and came to see that cultured meat could live side-by-side – using small herds of animals for environmental land management and for donor cells for cultured meat to be a by-product.

“My view was that we could replace some of the industrial meat system with a new technology and limit the environmental burden that agriculture has on our planet. We also still need some industrial agriculture for the process, feedstocks to feed the cells can also come from plants, it’s not a technology that sees a dissolution of agriculture but an evolution.”

Bringing (cultured) meat to market

Having set up Cellular Agriculture Ltd so soon into their collaboration, Prof Ellis and her team benefitted from insights into the food industry almost from day one. Perhaps unsurprisingly, this has given their research a focus on delivering impact.

“We’re working with a farmer, working with the food industry and other scientists including social scientists, trying to understand this from every perspective as far as we can. And we’re doing things in a way that will work in the food industry, because food is a massively complex integrated supply chain,” she says.

“There is a risk as a lab-based researcher that you can sometimes come into work, and have all these great ideas and try some stuff out and think you can save the world, but you don’t actually talk to potential users and other people who will be affected by these ideas about what it's like on the ground in reality.

“By working with so many different experts, and combining with a network bringing in so many views, definitely brings a completely different perspective to what we can do and how we think we should do it.”

For Prof Ellis, this not only means delivering processes and products that will be economic, sustainable and popular with consumers, but making sure that the food produced from culturing is genuinely healthy and nutritious.

Another way that they have differentiated themselves is in taking a long view, as Dunsford describes:

“We’ve combined the rigour of academic research with an industrial view of food production. It allowed us early on to concentrate on the question of scale rather than the current race to market that we see in getting products to regulation and into restaurants.

"Our aim has always been to focus on the long term, making cultured meat a reality in local grocery stores, available to all and as a tool to feed a growing global population. Ours is a marathon and not a sprint, and for that reason it takes time. We’re one of the oldest cultured meat companies globally and in our time we’ve seen many successes and failures, I hope we’ve chosen the right path for a strong foundation for the future.”

Nevertheless, cultured meat products are rapidly developing and in 2020 Singapore became the first place on Earth to permit the sale of cultured meat – in this case chicken nuggets – to the general public. Since then the company has received further permission to sell cultured chicken breast and shredded chicken.

For now this foray into the market remains limited, with small quantities sold for a high price compared to other meat products. But the approval is significant, and although the problem of scalability still needs solving, Prof Ellis says she wouldn’t be surprised to see firms apply to sell cultured meat in the UK within the next year or two – meaning we might be able to buy it in UK restaurants as early as 2025.

“I think it is going to happen,” she says, “It will then be a question of what is the product and is it not only good to eat but crucially also sustainable and ethical? That will influence longevity in terms of commercial sustainability - how is this actually going to work longer term?

“A lot of it will come down to the commercial opportunities, actually, so it's where can we align the sustainability and ethics with that commercially?

“It's happened in Singapore, it will happen elsewhere in the world, pretty soon the UK is going to want to be part of that.”

Research papers

Decellularized grass as a sustainable scaffold for skeletal muscle tissue engineering. Allan, S., Ellis, M. & De Bank, P., 31 May 2021: Journal of Biomedical Materials Research - Part A.109, 12, p. 2471-2482

Bioprocess Design Considerations for Cultured Meat Production With a Focus on the Expansion Bioreactor. Allan, S., De Bank, P. & Ellis, M., 12 Jun 2019: Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems.3, p. 1-99 p., 44.

Bringing cultured meat to market: Technical, socio-political, and regulatory challenges in cellular agriculture. Stephens, N., Di Silvio, L., Dunsford, I., Ellis, M., Glencross, A. & Sexton, A., 31 Aug 2018: Trends in Food Science and Technology.78, p. 155-16612 p.

Lab images by Laurie Lapworth / University of Bath

Lab video by Simon Wharf / University of Bath