Investigating Big Tobacco's influence

on public health

Research from the University of Bath is helping to reduce smoking and save lives, from informing public policy, such as the ban on smoking in pubs, to the introduction of standardised packaging for cigarettes.

"A uniquely deadly product"

Smoking kills. That message might seem so obvious that the scale by which it devastates lives can be overlooked. Yet in 2022 – some seventy years since the links between smoking and lung cancer were first revealed – more than eight million people still die every single year as a result of tobacco use or passive smoking.

The statistics speak volumes: 1.3 billion people, more than a fifth of the world’s population, smoke. 80% of those live in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs). At least half of them will die as a result. Little wonder the World Health Organization (WHO) describes the tobacco epidemic as ‘one of the biggest public health threats the world has ever faced.’

Such stark realities form the backdrop to the work carried out by the University’s world-renowned Tobacco Control Research Group (TCRG). Since 2007, TCRG has been researching how the actions of so-called ‘Big Tobacco’ – the largest global tobacco firms – contribute to the epidemic and undermine public health.

The group was set up and is led by Anna Gilmore. Professor of Public Health and a leading international expert on the commercial determinants of health – the ways in which the commercial sector impacts on health, including by influencing policies - Prof Gilmore has had the tobacco industry and its role in causing preventable disease firmly in her sights for over two decades.

"Tobacco is the only legal consumer product that kills up to half its users when used exactly as the manufacturer intends."

“It all started during my time working as a junior doctor in a busy hospital," she explains. “I realised then that so many patients I was seeing were coming back time and again with the same health conditions because they smoked. Treatment options just felt like a plaster on the wound. It was clear that what we needed was more effective preventive interventions.”

That realisation set Prof Gilmore on a career change, away from frontline medicine, towards public health. A diploma in tropical medicine, followed by a stint working in Tibetan refugee camps in Nepal and a hospital in rural India, preceded a prestigious research secondment which would focus on the tactics deployed by the tobacco industry to promote smoking.

Through that secondment, carried out at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, Prof Gilmore was one of the first to access previously secret tobacco industry documents. Thousands of private internal memos had been made public following a landmark US lawsuit in the early 2000s.

What they revealed would shock many.

"A wolf in sheep's clothing"

“People at this point knew that smoking was bad,” says Prof Gilmore – research into the links between smoking and cancer first emerged in the 1950s – “what was different, though, was that with these documents we could see the industry’s research misconduct, the extent of their marketing, their involvement in cigarette smuggling on a massive scale, and how they were seeking to influence policy changes at multiple levels.”

One of her first projects looked at how the tobacco industry was operating in former Soviet Union countries following the collapse of the USSR. Her analysis of industry documents highlighted two clear trends: the extent of their advertising efforts in newly opened markets, and the direct effect this was having on skyrocketing smoking rates.

“You could just see very clearly how smoking increases in women were directly mirroring the industry’s marketing plans. Their tactics were working,” says Prof Gilmore. Her research highlighted how at the time 75% of plastic bags in Russia and 50% of billboards in Moscow carried tobacco adverts, and how there was a big push to attract new female smokers.

Elsewhere, the documents highlighted the great lengths to which the industry had gone to intervene in public health policies which threatened their business. In Uzbekistan, for example, her research showed how direct appeals to the country’s President overturned legislation curbing cigarette advertising and smoking in public places literally overnight.

“Through these documents not only could you see how the industry was using marketing to ramp up its sales, but you could also see clearly how they were forcing themselves into new markets - often using smuggling to do so - advocating to replace former state monopolies with their own, and intervening in policy to suit their business interests. It was a real revelation.”

Read more about this research.

Watch Anna Gilmore at the launch of Bath's IPR discussing this research.

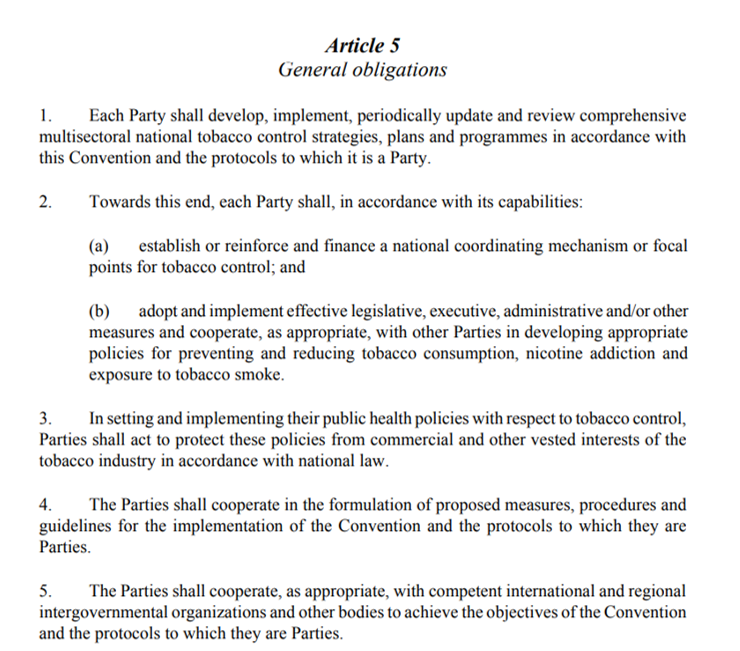

Some of this work contributed to the development of the seminal Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC). Developed by the WHO as the first ever global treaty on tobacco control, since its adoption, in 2003, it has become one of the most widely embraced treaties in the UN’s history.

Its Article 5.3 – which sets out requirements to prevent the tobacco industry from influencing public health policy – remains a key reference point for public health two decades on. ”Article 5.3 really changed people’s thinking on the tobacco industry – it helped cement the industry as a part of the problem and, as such, it moved tobacco control on,” explains Prof Gilmore.

It was in this context that the then Dr Gilmore moved to Bath and TCRG was formed. Whereas most tobacco control researchers up to that point were focused on ‘demand side’ issues - changing individuals' smoking habits - TCRG would soon become a leading voice in tackling ‘supply side’ ones – uncovering how it was the industry’s behaviour driving the problem.

New policy challenges

Having recruited a team of multidisciplinary, international public health experts, including statisticians and even two investigative journalists, TCRG soon began to influence policy changes nationally and internationally. One of its first big projects and significant impacts was its evaluation of smokefree legislation in the UK.

On 1 July 2007, the UK passed pioneering legislation making it illegal to smoke in enclosed workplaces and public spaces, most notably in pubs and clubs. Designed to save lives by reducing the effects of second-hand smoke, at the time it was one of the most ambitious policy changes in the world.

For proponents, the law was crucial in reducing the burden of passive smoking, which increases the risk of heart disease and lung cancer by nearly 25%. But detractors lobbied hard for it to be rolled back, citing the negative economic impacts on hospitality venues. With a change of government in 2010 came a real risk that legislation might be pared back.

Prof Gilmore highlights TCRG’s evaluation of smokefree, which showed a reduction in hospital admissions for heart attacks, as one of the Group’s first ‘big hits’. Not only were these research findings significant domestically in helping to safeguard smokefree legislation, but, with other countries looking on, they would be influential in shaping emerging, international policies too, as well as future policy evaluations.

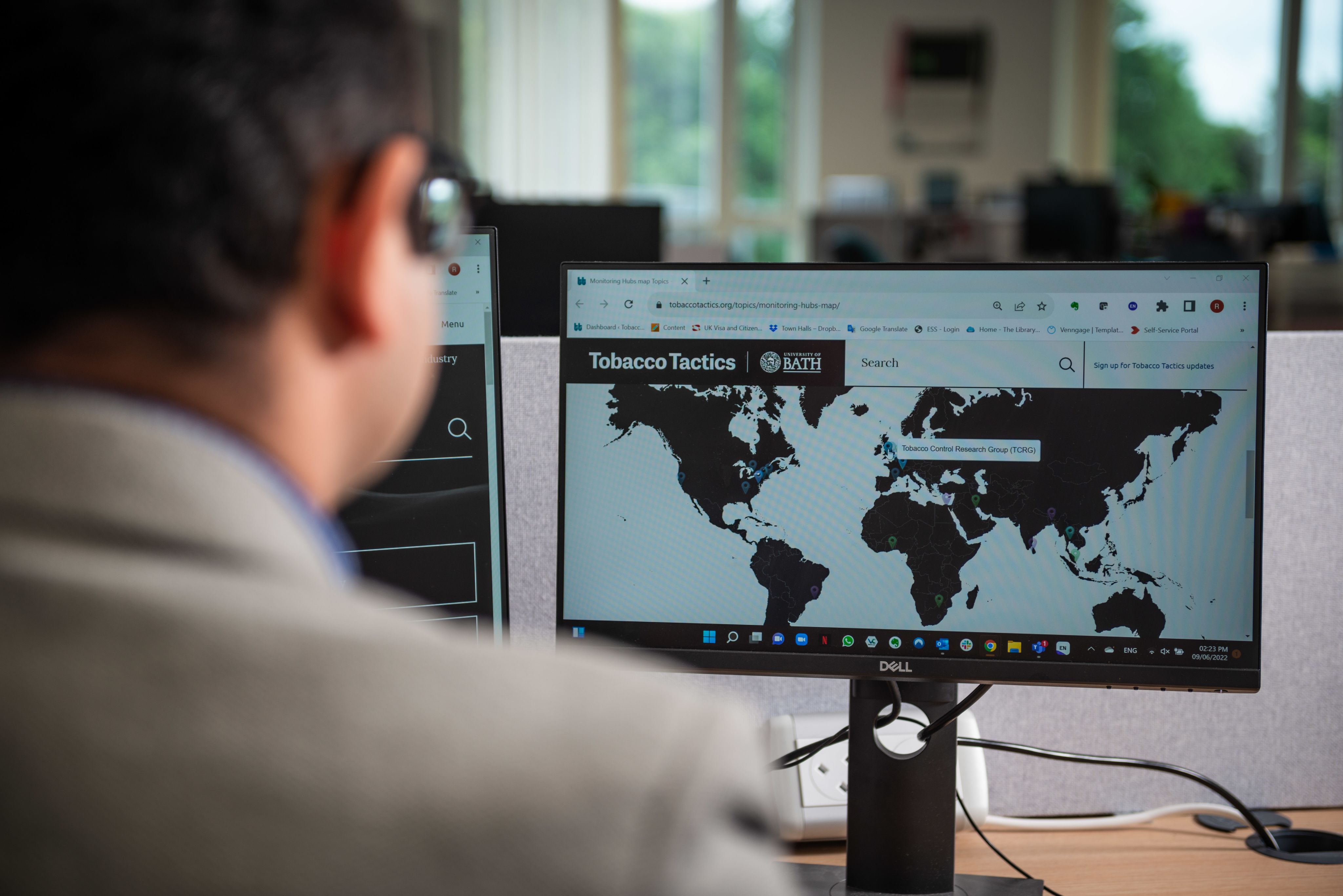

Shortly after, the team developed a whole new approach to disseminating its research and evidence to policy audiences. Establishing TobaccoTactics – a Wikipedia-style website documenting bitesize insights about the tobacco industry, its affiliates or ‘front groups’, and emerging policy issues – helped to fast-track the policy influence their work had.

”We realised we needed something more immediate that could accompany our academic papers and help to share knowledge and expertise with a policy community,” explains Prof Gilmore. As word got out, traffic to TobaccoTactics increased and it quickly became the go-to place for policymakers, advocates, journalists and fellow researchers working on tobacco control issues.

For example, when the EU’s Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) – which regulated how tobacco could be sold requiring large warning labels and banning flavours - was being finalised in 2014, TobaccoTactics was used extensively by the MEPs involved. “When individuals or groups lobbied about the TPD, policymakers would check their links to the tobacco industry by searching TobaccoTactics,” recalls Prof Gilmore.

Set up a decade ago, the site recently had a major revamp. Over the past two years it has attracted 1.3 million page views and 800,000 users from practically every nation on earth. Across 900 pages it is a unique resource that charts the tactics, strategies, major products and key personnel of the tobacco industry and its allies and front groups.

“No other research site boasts the collective memory of so much global monitoring and investigation. Through articles, maps, databases, animations and graphics it is a key point of reference for public health officials, academics and journalists to hold the industry to account.”

"A smoke and mirrors web of misinformation"

(Video by Kmeel Stock)

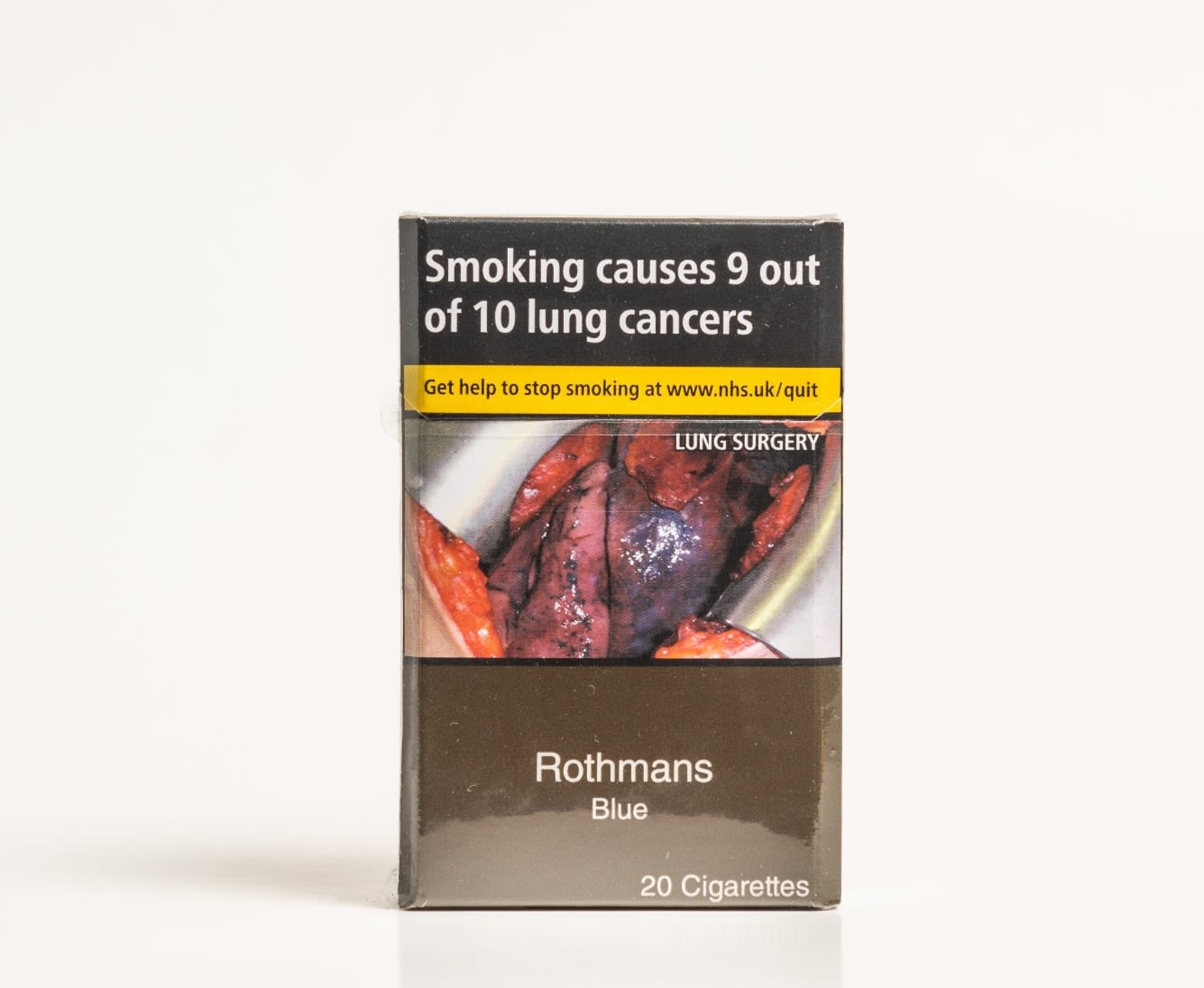

As the TPD went through the EU in 2014, so too were debates heating up in the UK about the introduction of standardised packaging for cigarettes. Aiming to reduce the appeal of smoking, introducing ‘plain’ standardised packs would replace bright insignia emblazoned on packaging with dull uniform ones carrying prominent health warnings.

Already made law in Australia in 2012, proposals for its introduction in the UK, which first emerged in 2008, quickly heralded a strong backlash from the tobacco industry and its associates. Their arguments centred on claims that plain packs would increase smuggling and organised crime, sound a death knell for small retailers, whilst also doing little to dent smoking rates.

Many of these arguments put forward by industry swayed the government to stall the policy although, following protest, it commissioned former paediatrician, Sir Cyril Chantler, to review the evidence. Research from TCRG was able to challenge and debunk the industry's claims by analysing and assessing the evidence it was supplying. This research was provided to Chantler and was integral to the legislation progressing.

For example, one TCRG research paper found that the industry was deliberately using scare tactics to cast doubt about the potential effectiveness of standardised packaging. This revealed how over five years the tobacco companies had placed misleading media stories exaggerating the scale of illicit tobacco in the UK, whilst also downplaying its own role in tobacco smuggling.

The analysis was corroborated by independent data from the Australian Borders and Customs Agency. Contrary to their claims, this showed that plain packaging in Australia had not heralded a sudden spike in smuggling. By further assessing industry submissions, the Group found additional issues with the claims made.

For instance, their argument that retailers would be forced out of business as customers were required to wait longer to buy cigarettes, was not only unsupported by evidence, but was also submitted by organisations directly funded by the industry – so called ‘front groups’ (something these organisations also failed to disclose in their submission).

As for plain packaging’s likely effects on smoking, analysis from TCRG published in PLOS Medicine found that industry submissions misrepresented or misquoted research. It also showed that the industry's evidence claiming standardised packaging would not work was of poor quality: of 77 items of evidence they submitted to the government consultation, only 17 addressed the impact on smoking of standardised packaging, 14 of these were industry-funded and none were peer-reviewed.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the industry’s own submissions also failed to include its internal evidence about the effectiveness of cigarette packaging as a key marketing tool. In 1994, at a Philip Morris International event, marketer Mark Hulit had made that clear, stating: ‘Our final communication vehicle with our smoker is the pack itself… our packaging is our Marketing.’

In April 2014, Chantler reported back that the weight of evidence pointed only in one direction: plain packaging would deter smoking and should be introduced. Less than a year later, MPs in the Commons voted in favour of plain packaging and legislation was subsequently accepted by the House of Lords.

But not before one final twist in the road.

Two months after passing through Parliament, Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco filed lawsuits challenging the proposal, citing projected loss of income and breach of intellectual property. They were joined by Japan Tobacco International, who argued that plain packaging infringed UK obligations under World Trade Organization rules.

These legal claims were rejected in the High Court, which in its ruling relied on two key pieces of TCRG research to conclude that evidence submitted by the tobacco industry to the public consultation on plain packaging ‘generally fell below best practice’ (see point 375, p180).

After a lengthy battle, plain packaging legislation finally came into force on 20 May 2016.

Counting the costs of smoking

TCRG’s work has also had significant impacts on tobacco pricing.

Raising the price of cigarettes reduces consumption and thereby improves public health. That is one of the main reasons why governments around the world have raised taxes on tobacco products. Yet the tax equation when it comes to tobacco is not as simple as it seems.

In 2009, TCRG first identified a knowledge gap in industry pricing. "I was reading tobacco industry journals [trade magazines] documenting how they were making cheaper products, but I also knew their profits were going up. Given that overall sales were falling, this just didn’t stack up," says Prof Gilmore.

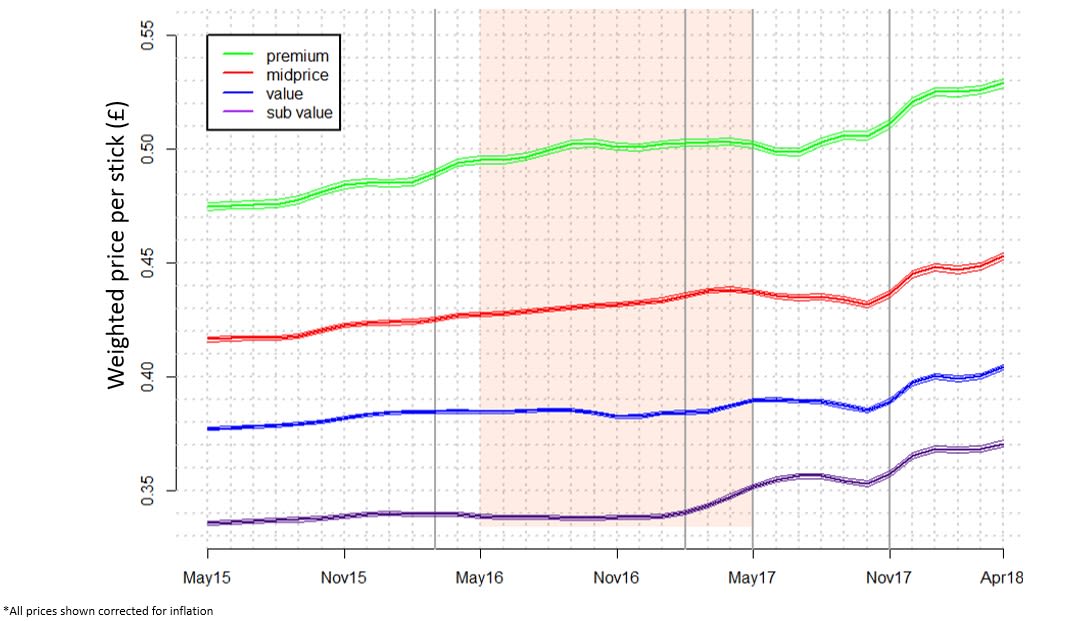

TCRG research into this topic highlighted three key findings:

- Firstly, UK national survey data revealed the cheapest products were smoked mostly by the young and the poor. However, prices on these products were not rising in-line with increased taxes. The tobacco industry was instead absorbing tax increases on these cheap products to keep them affordable.

- Secondly, prices on more expensive, premium brands, were rising more than needed. The industry was ‘over-shifting’.

- Thirdly, the price rises of expensive brands, coupled with the high sales of cheap brands, was allowing companies to increase their overall profits despite increases in tax.

Prof Gilmore took these findings to the Treasury along with a recommendation for the introduction of a Minimum Excise Tax (MET) – a higher minimum level of tax on cigarettes - so that if tobacco companies sold products cheaply, they would still pay tax and lose revenue.

This research was critical in providing the evidence to convince the Treasury of the need for a MET. Since its implementation in 2017, TCRG's evaluation shows that the MET has helped to increase prices of the very cheapest brands; something Prof Gilmore says will be crucial in driving down health inequalities in the years ahead.

TCRG analysis showing prices of the cheapest cigarettes (sub value) rising when the UK implemented a MET in May 2017.

TCRG analysis showing prices of the cheapest cigarettes (sub value) rising when the UK implemented a MET in May 2017.

Further research from the Group also showed the MET stopped the previous growth in cheap cigarette sales and helped to reduce sales overall.

Other work from Prof Gilmore on tobacco pricing, along with colleagues Professor Rob Branston and Dr Rosemary Hiscock, has pushed forward a system of price cap regulation to counter the excess profitability of the tobacco industry. Their work has also highlighted disparities in tax and in price paid on different tobacco products, notably on roll-your-own tobacco (RYO).

Prof Branston discussing TCRG research on radio.

Most recently, in June 2022, some of this analysis found its way into the high-profile government-commissioned Khan Review: Making Smoking Obsolete. Its recommendations for sharp, sudden increases on tobacco tax and the importance of matching tax between RYO and factory-made cigarettes draws heavily on TCRG research, as does its call to 'make the polluter pay'.

While the UK already has relatively high prices (a pack of 20 factory-made cigarettes now costs £12.64 on average), they are still much cheaper than places like Australia and New Zealand where they can cost double.

"The burning injustice of influence"

* Footage of tobacco sifting in Malawi from an upcoming TCRG film by

Professor Roy Maconachie (Department of Social & Policy Sciences) and Simon Wharf (Bath's AV Unit) .

As regulations constrain how the industry operates in many parts of the world, many see it as having shifted its focus to target emerging low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where tobacco sales are still growing. To keep pace with this change, how the industry operates across Africa, Asia and South America now forms a large part of TCRG’s work.

Through the Group’s involvement as the research partner in STOP – a global tobacco industry watchdog established by Bloomberg Philanthropies in 2018 – the team is now playing a leading role in sharing knowledge and expertise about the tobacco industry internationally. Its research helps STOP achieve its aim of providing stakeholders with evidence-based research to inform public policies.

With STOP partners, including the Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control, TCRG has played a key role in the Global Tobacco Industry Interference Index - the UK work for which is led by Dr Raouf Alebshehy.

It is also continuing to deliver its campus-based training on tobacco industry monitoring, research and accountability. To date, TCRG has trained more than 75 people from 51 countries, significantly building capacity to address tobacco industry interference. So successful was the model that the Secretariat to the FCTC used it to set up a series of Observatories in 2017.

"From our research we know the main arguments the industry is likely to make when it comes to new legislation. This playbook may vary somewhat on context, but we are increasingly able to second guess their tactics. STOP is helping us to globalise our work and we’re able to help LMIC countries to build their own capacity," says Prof Gilmore.

Read more about this research.

Tobacco industry monitoring centres from LMIC countries attending one of the training courses with TCRG at the University of Bath in 2017.

Tobacco industry monitoring centres from LMIC countries attending one of the training courses with TCRG at the University of Bath in 2017.

"Few people back in Sri Lanka had heard of Bath, let alone the University of Bath. But tobacco prevention campaigners do know about its Tobacco Control Research Group. For me I always wanted to come to the fountain of my inspiration in tobacco industry research and monitoring and the week in Bath was hugely valuable as we take this work forward."

Prof Anna Gilmore with Dr Raouf Alebshehy in the TCRG in 2022.

Prof Anna Gilmore with Dr Raouf Alebshehy in the TCRG in 2022.

Through STOP, TCRG has also been able to reach a wider global audience.

In 2021, two STOP reports led by TCRG focused on issues of corruption in Africa. These reports and underlying in-depth research were used to inform two BBC Panorama documentaries, which exposed allegations of wrong-doing and attempts to influence policy.

Based on analysis of revelations from whistle-blower documents and court records, the documentaries raised major concerns about the industry’s alleged conduct in Africa.

In 2022, the investigation by TCRG, the BBC and Bureau of Investigative Journalism was longlisted by Private Eye for its acclaimed Paul Foot Award.

Members of the TCRG with Private Eye's Ian Hislop at the Paul Foot Award ceremony 2022.

Members of the TCRG with Private Eye's Ian Hislop at the Paul Foot Award ceremony 2022.

"Programmes like Panorama have helped our work reach an audience of millions around the world and it’s changed the standing of the industry," says Prof Gilmore. "Our research has been able to shine a light on these activities, but investigative journalists have been able to go places and reach people we simply couldn’t."

For its impacts, last year TCRG was given a special recognition by the Director-General of the WHO in its prestigious World No Tobacco Day Awards.

This year, for the second year running, WHO again recognised its contributions with a posthumous honour for Dr Mateusz Zatoński – an aspiring public health researcher with TCRG who tragically died in 2022.

The late Dr Mateusz Zatoński, Research Fellow, Tobacco Control Research Group, University of Bath.

The late Dr Mateusz Zatoński, Research Fellow, Tobacco Control Research Group, University of Bath.

Broadening scope

Whilst TCRG’s work on tobacco continues apace – and there are emerging issues including the tobacco industry’s role in e-cigarettes and other new products - the team is now increasingly turning its attention to other aspects of the commercial determinants of health – from fast food to gambling.

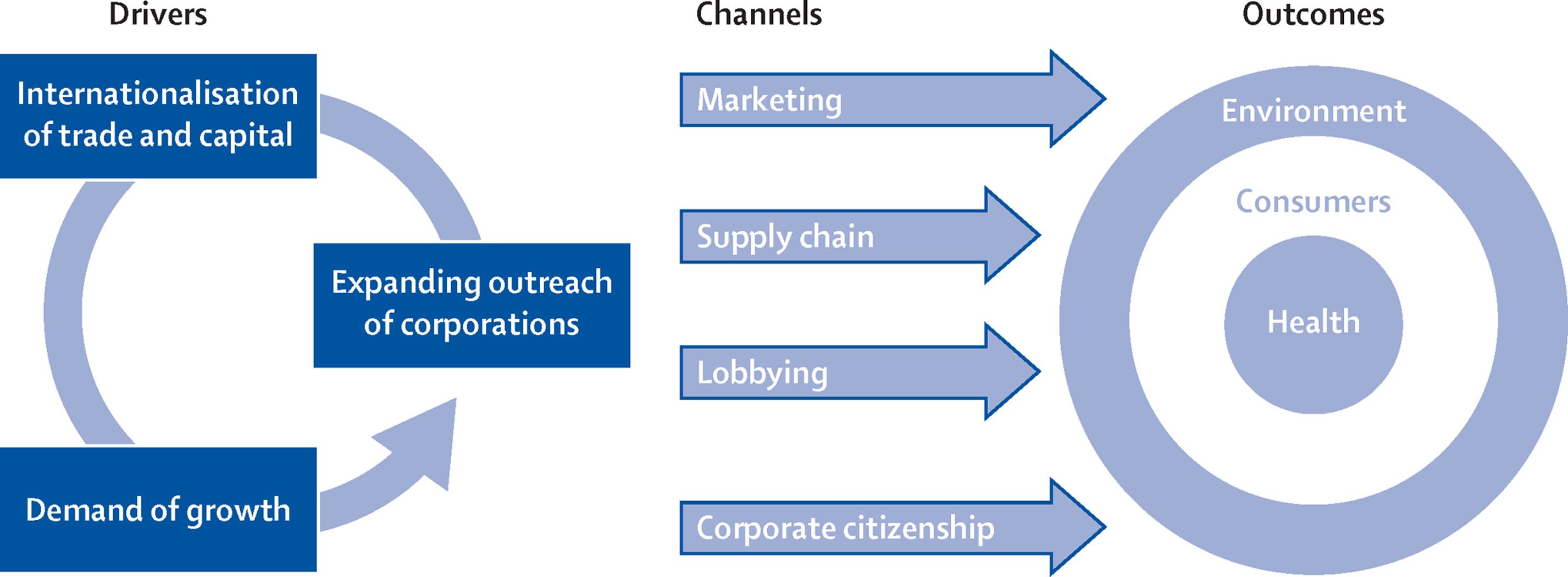

Kickbusch, Allen and Franz's (2016) figure of the dynamics that constitute the commercial determinants of health.

Kickbusch, Allen and Franz's (2016) figure of the dynamics that constitute the commercial determinants of health.

Recent research from TCRG's Tess Legg has exposed how corporations from many sectors – alcohol, chemicals, extractive, food and drink, fossil fuel, gambling, pharma and tobacco - repeatedly and consistently engage in the same practices to influence science and how it is used in policy in their own interests. Her typology provides a simple way to understand this and highlights the need to protect science from vested interests.

Other research, from TCRG's Dr Kathrin Lauber, has looked at the sustained efforts of the food and drinks industry to oppose public health measures which aim to tackle heart disease, cancer and diabetes. This is a burgeoning area of research, and one which Prof Gilmore is keen to ensure has as much policy influence as tobacco.

“Ensuring impacts from research in this area is all about understanding in detail the issues that policymakers face, being networked and spotting where the gaps in knowledge are. It relies on both timely research, but also how embedded you are as part of a network of organisations working on similar themes. You really can’t achieve anything in isolation,” she says.

And as for Anna Gilmore, what is it that sustains her focus on this topic?

"It’s the massive injustice of it all, the fact that it’s putting at risk the lives of millions, including the poorest people in societies. If we’re serious about improving health in the long-term, we have to keep shining a spotlight on the role these industries are playing in driving ill health and undermining public health efforts to tackle it."

Research papers

Longitudinal evaluation of the impact of standardised packaging and Minimum Excise Tax on tobacco sales and industry revenue in the UK - Hiscock, R. Augustin, N. Branston, J.R., Anna B. Gilmore (2021): BMJ Tobacco Control

The Science for Profit Model - How and why corporations influence science and the use of science in policy and practice - Legg, T., Hatchard, J., Gilmore, A. (2021): PLOS One

The Policy Dystopia Model: An Interpretive Analysis of Tobacco Industry Political Activity - Ulucanlar, S., Fooks, G., Gilmore, A. (2016): PLOS Medicine

Tobacco industry manipulation of data on and press coverage of the illicit tobacco trade in the UK - Rowell, A., Evans-Reeves, K., Gilmore, A. (2014): BMJ Tobacco Control

Understanding the vector in order to plan effective tobacco control policies: an analysis of contemporary tobacco industry materials - Gilmore (2012): BMJ Tobacco Control.

Images by Laurie Lapworth / University of Bath unless credited.

Video by Simon Wharf / University of Bath.