Stemming the flow of drugs into prisons

We're developing the world's first portable device that detects synthetic drugs.

Dr Chris Pudney is developing a tool that could help turn around the lives of some of the most vulnerable people in society.

His inter-disciplinary team at the University of Bath is developing the world’s first portable test that detects synthetic drugs such as Spice.

They’re hoping that in the future the device will be used to help stem the flow of synthetic drugs smuggled into prisons and reduce the devastating effects on users of these highly addictive substances.

Spice is the street name for a mixture of lab-made drugs known as synthetic cannabinoids or Novel Psychoactive Substances (NPS). They mimic the effects of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive ingredient of cannabis, by binding to the same receptors in the brain.

Whilst they were originally designed to mimic the effects of cannabis, they are much stronger which makes them considerably more dangerous and unpredictable.

They can cause severe negative effects including anxiety, paranoia and psychotic episodes.

THC is known as a partial agonist because it only partially reacts with cannabinoid receptors, however synthetic cannabis binds more strongly to the receptors and activates a full response, causing much more intense effects.

A totally different drug

Natural cannabis from plants contains a concoction of chemicals – in addition to THC, it contains cannabidiol (CBD), which is marketed as a medicinal treatment for a whole host of health problems, from pain relief to Parkinson’s disease.

“Synthetic drugs like Spice are often mistaken for a synthetic version of cannabis, but in reality, they are completely different drugs,” says Dr Pudney, Reader in the University’s Department of Biology & Biochemistry.

The synthetic drugs are sprayed onto dried leaves which users can smoke, but as there is no quality control by sellers, the effects can be very unpredictable.

Dr Pudney says: “Our studies have found that there is a huge variation in strength of these drugs, even within the same batch. This means users have no idea how strong it is or how much they’re taking.”

“A particularly unpleasant drug”

Dr Jenny Scott is a Senior Lecturer from the Addiction and Mental Health Group based in the University of Bath’s Department of Pharmacy & Pharmacology. Alongside her academic research, she works in a drug and alcohol treatment clinic one day a week.

She has been working with Dr Pudney on the synthetic drugs test from the start, to understand the use of these drugs in more detail so they can create a device that meets the needs of the people that will be using it.

Interviews with frontline homeless workers in Manchester in 2016 estimated that between 80 and 95 per cent of homeless people in the city centre were using synthetic cannabinoids.

Dr Scott says: “Spice is cheap and very easy to buy online from abroad, but it’s a particularly unpleasant drug.

“Not only is it more harmful than cannabis, but it’s more addictive and poses severe health risks for users.

“The negative effects can be so strong that most people who try it, don’t usually repeat the experience,” she says. “People only take it if they’re really desperate to separate themselves from their reality.

“If you’re homeless, sleeping in a doorway, you might be subjected to physical or verbal abuse, urinated on, have your possessions stolen, or even be raped. Powerful synthetic drugs like Spice zombify users to help them cope with the grim reality of life on the streets or in prison.”

The first synthetic cannabinoid was identified on the recreational drug market in 2008. It was swiftly banned in many countries however as soon as one substance was outlawed, another similar chemical with the same effects would appear on the drugs market.

This initially gave Spice the reputation of being a 'legal high' because legislators were always playing catch-up.

The 2016 Psychoactive Substances Act put a stop to this in the UK by making it an offence to produce, supply, import or export any psychoactive substance, with the maximum penalty being seven years' imprisonment.

The law stopped the sale of synthetic drugs in high street shops, and reduced their use in the general population, but they are still very prevalent in highly deprived areas, in particular the homeless population.

"The ban hasn't changed anything. … It's not stopping people from taking it [synthetic cannabinoids], ... It's just changed where people get it from."

Because they're cheap and not easily detectable, their use in the community is difficult to monitor or control.

It also means they can easily be smuggled into prisons.

“Because until now it’s been difficult to detect these drugs, they are the most commonly used substances in prisons,” says Dr Scott.

“Inmates use it while in prison, if they come out homeless, as many do, they may keep taking it as it’s cheap, easy to get and it’s not routinely tested for.”

People smuggle the drugs into prison by spraying them onto letters, children’s drawings or pieces of clothing or books to take into the prison or onto faked legal documents, because prison rules state that legal documents must only be opened by the recipient.

Rules have recently changed so that photocopies of all post except legal documents are given to inmates instead of the originals, and greetings cards can only be sent directly from approved online suppliers. However, drugs still get into the prisons via other routes.

“These are organised gangs of criminals that are smuggling drugs into the prisons – they are creative in finding ways of getting through the system,” says Dr Pudney.

“People soak paper or clothing in drugs and then throw them over the fences, or tamper with external contractor services such as the laundry or maintenance.

“Whilst there is drug testing equipment already in prisons, they only check for specific drugs, and you can only test as many things as you can swab – and you can’t swab everything.

“In contrast, our detection device identifies a range of synthetic drugs in saliva, on paper or fabric, in an instant, simply by waving it over the top of the sample – we hope it could be a real game-changer in the fight to keep drugs out of prisons.”

From protein detection to drug detection

Chris Pudney isn’t a small-molecule chemist – he’s a biochemist who normally works on detecting proteins – but he came up with the project after a chance conversation with his partner, Amy, in 2019.

He says: “My partner’s a psychiatrist and she often gets called to Accident & Emergency departments to assess patients presenting with severe psychosis.

“She was telling me how it’s a real problem when people come in that may have smoked Spice but it’s impossible to tell for sure what they’ve taken, meaning it’s difficult to decide what treatment pathway is best.

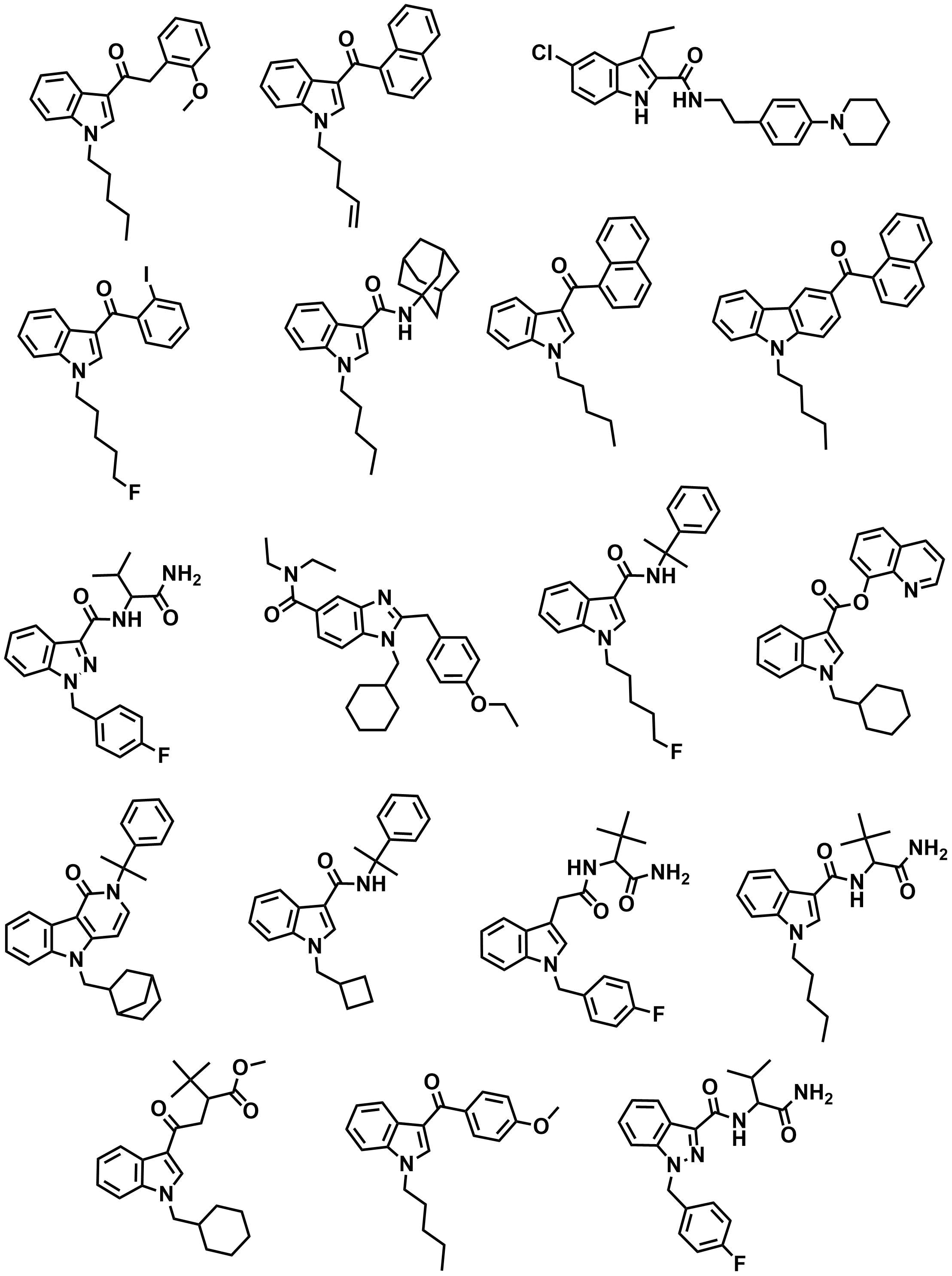

“When I looked up the chemical structure of these molecules, I was amazed to see that the core part looks a lot like a molecule called Tryptophan, found in proteins, which fluoresces under UV light.

“All of a sudden, I knew how we could solve this. I went back to the lab and tried throwing some molecules that looked a bit like these a under UV lamp, and they glowed like a dream.”

Dr Pudney set to work building a handheld UV measuring device knocked together using spare parts in his lab.

Tryptophan is an amino acid found in most proteins that fluoresces under UV light. When UV is shone onto the molecule, the electrons in the ring structure become excited and emit visible light that can be detected in a fluorimeter.

The core part of the synthetic cannabinoid molecule is structurally very similar to tryptophan and Dr Pudney discovered it had similar fluorescent properties too, meaning it could be easily detected in the same way.

Tryptophan is an amino acid found in most proteins that fluoresces under UV light. When UV is shone onto the molecule, the electrons in the ring structure become excited and emit visible light that can be detected in a fluorimeter.

The core part of the synthetic cannabinoid molecule is structurally very similar to tryptophan and Dr Pudney discovered it had similar fluorescent properties too, meaning it could be easily detected in the same way.

Simple, robust device that detects in seconds

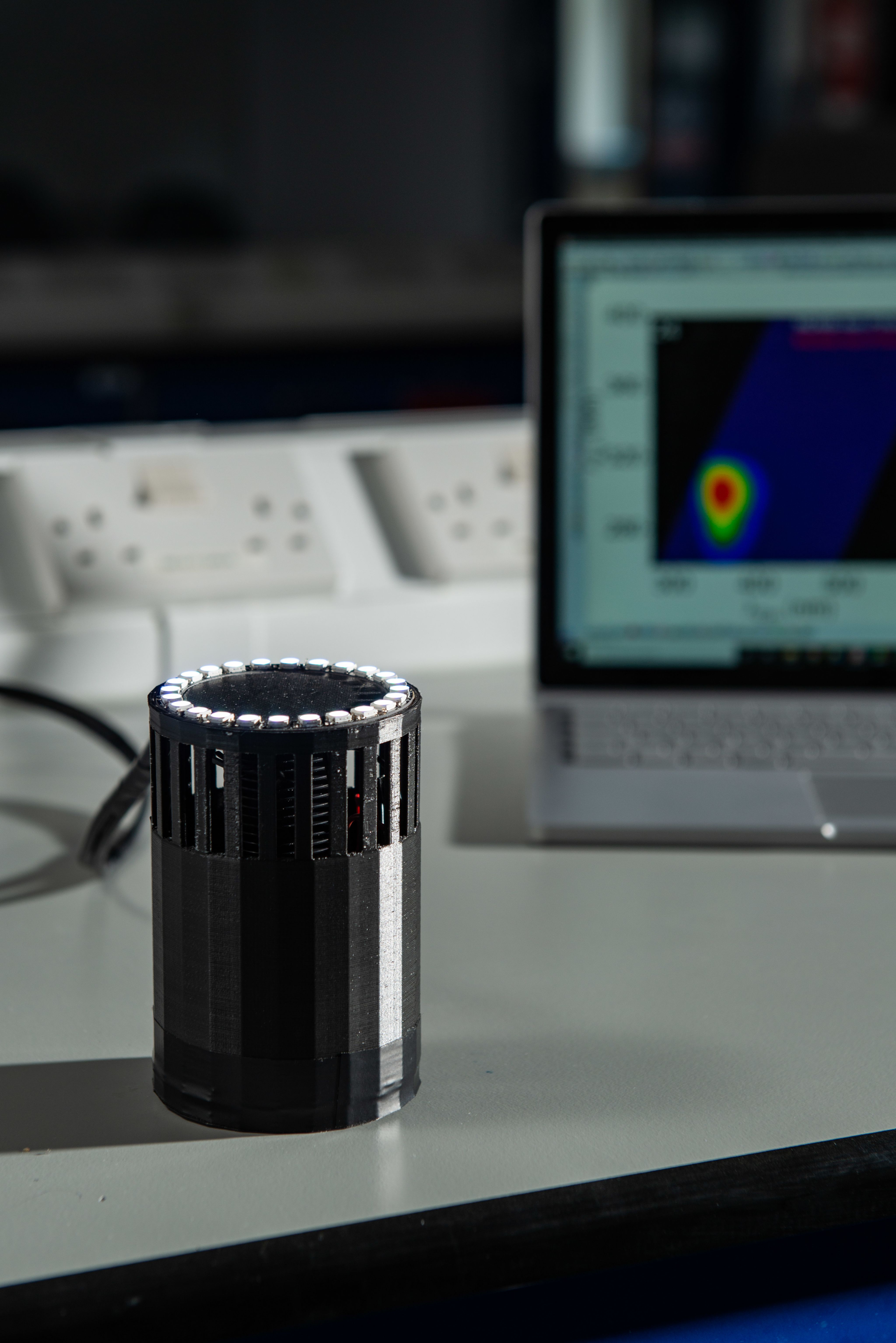

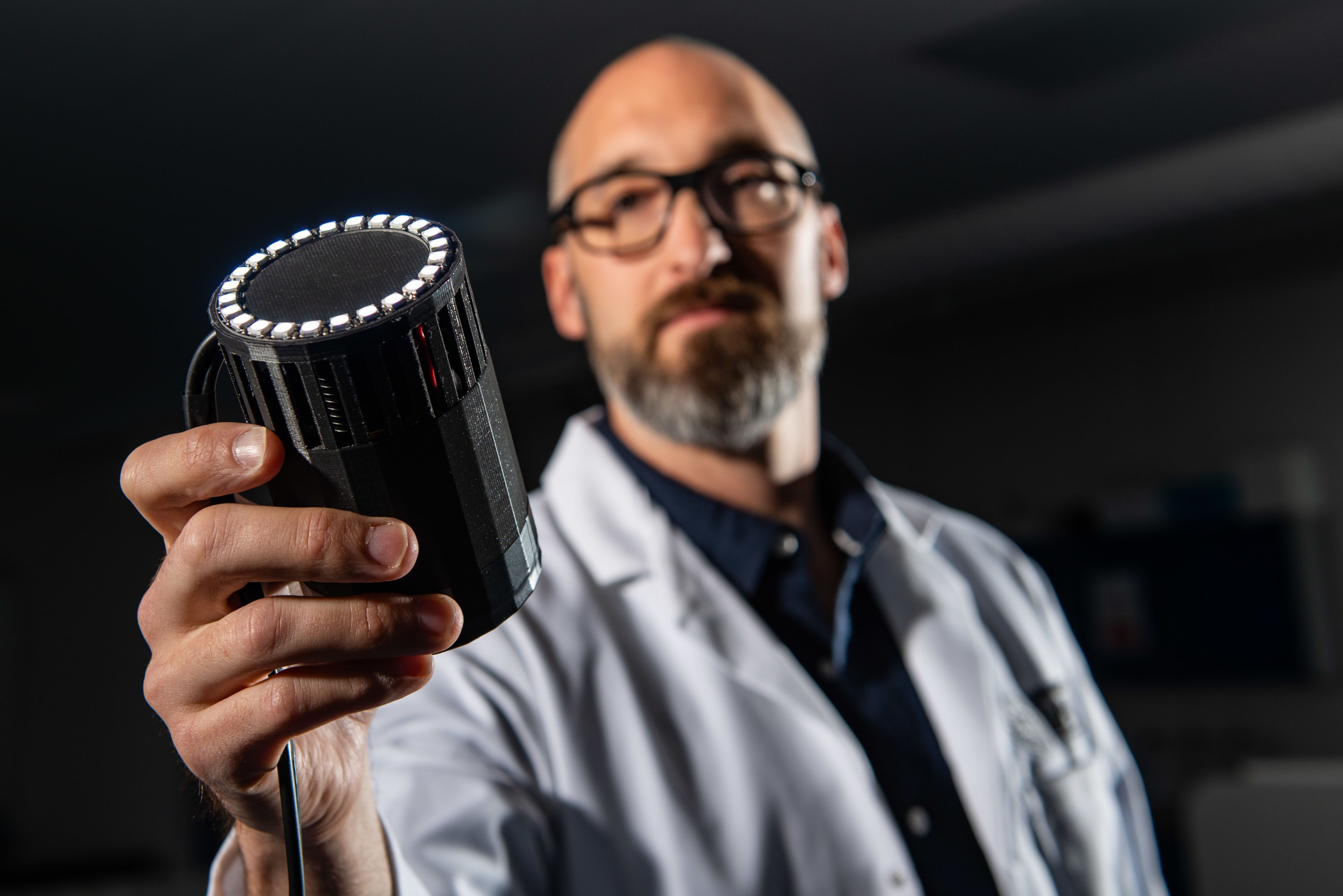

The device is cylindrical, measures 10 cm in length and has a ring of LEDs on the top.

When held over the sample, it shines UV light onto it and measures the fluorescent glow from the sample. If it detects synthetic cannabinoids, some of these lights turn red, depending on the strength of the sample.

Dr Pudney says: “Because Spice is a mixture of molecules rather than a single drug, this presented a real challenge when designing a system to detect them.

“But we’ve successfully managed to create a device that can detect a whole range of molecules, so if a new variant drug appears on the scene, we can still detect it.”

As well as the hand-held detector that tells you whether drugs are present or not, the team is also working on another version of the equipment that be hooked up to a computer to analyse the emitted light, and pinpoint which molecules are present.

Dr Pudney says: “Each type of synthetic drug molecule emits a slightly different spectrum of wavelengths, giving a unique spectral fingerprint.

“However most real-life drug samples contain a number of different substances, so we are now working with colleagues in the Department of Computer Science to use machine learning to analyse these spectral fingerprints, so we can identify exactly what mixture of molecules is present in each sample.”

Once they had a proof-of-concept test working on innocuous drug-like molecules, Dr Pudney started collaborating with Dr Scott's team to start testing the device on real drug material, seized by Avon and Somerset Police.

Dr Pudney says: “Working with the police to get authentic samples has been key to this project, so we have had real molecules to look at.

“One of our students even developed a ‘smoking simulator’ in the lab that has a pair of artificial lungs that inhale the burning material from a cigarette and trap the chemicals that come off.”

Since developing their first prototype in 2019, the team has been refining the device, 3D-printing a new version every few weeks or so.

The latest set up is able to detect synthetic drugs in saliva samples, on dried leaves, on paper, and on fabrics.

They have also successfully used it to detect synthetic cannabinoids in vape liquid, which is increasingly being used to take synthetic drugs, instead of smoking.

Credit: Laurie Lapworth

Credit: Laurie Lapworth

Credit: Laurie Lapworth

Credit: Laurie Lapworth

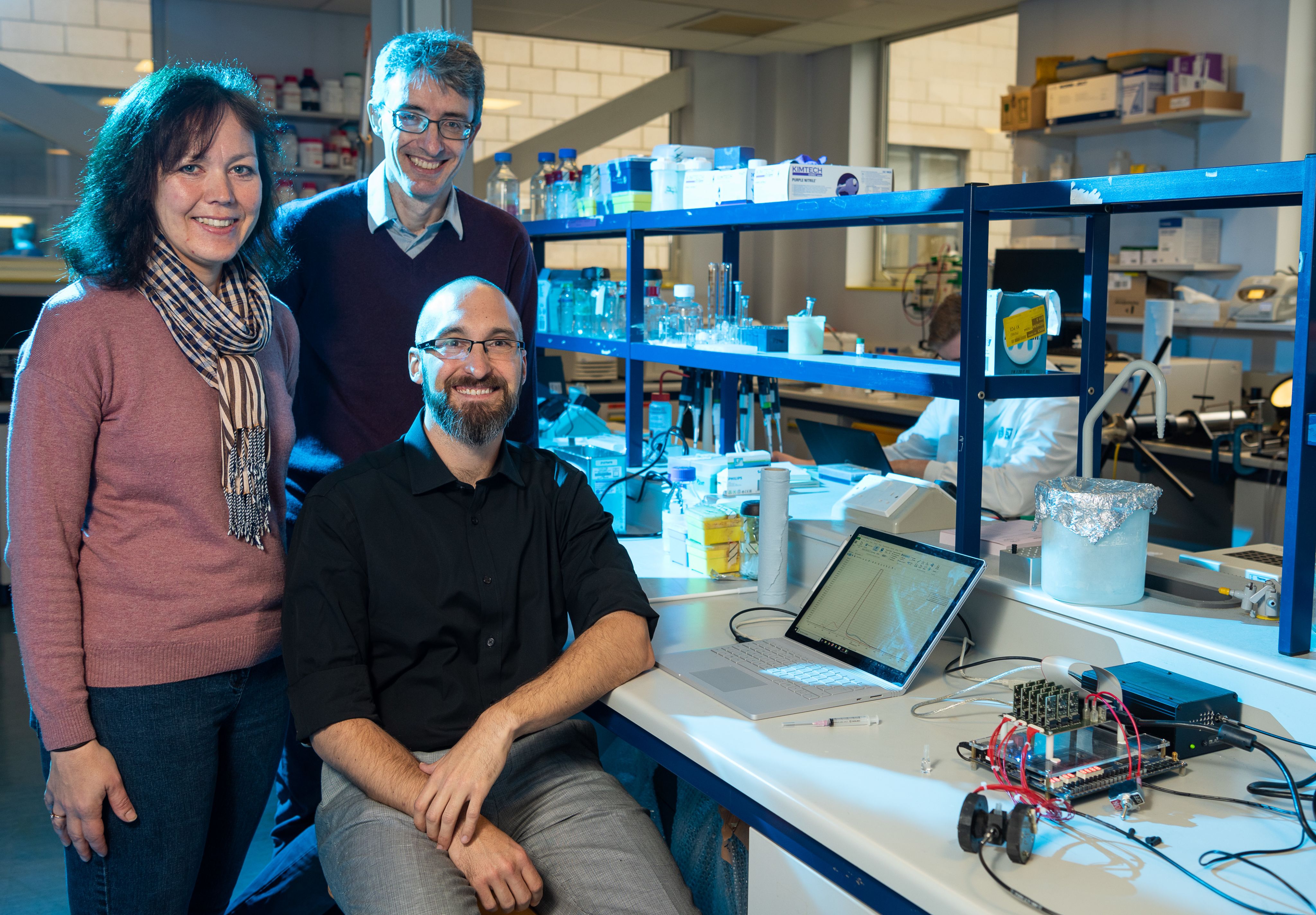

Cross-disciplinary research team

In order to develop a gadget that could be used outside the lab in clinical settings including pharmacies, it was particularly important for the team to ensure it was cheap to make, robust and simple to use.

A key advantage of working at Bath was that they were able to recruit experts to the team from across the University in a huge variety of disciplines: analytical and synthetic chemistry; optics engineering; machine learning; pharmacy practice; harm reduction and addiction psychology.

Dr Pudney says, “We are very lucky to have this wealth of expertise at Bath.

“We currently have around 15 people working on the project at the moment, with everyone tackling different parts of the problem, from engineering a piece of kit that works reliably in a low resource setting, to understanding the social problems of how and why people take drugs, so that we can design something that meets their needs.”

Dr Scott says: “This piece of kit will be used by pharmacists, healthcare professionals, prison officers and homeless shelter volunteers, so needs to be designed so it can be used by anyone and give reliable results every time.”

The kit also needs to be robust enough to survive being dropped, so the team even tested it by throwing it against a wall, which thankfully it passed.

Finally, the device needs to be inexpensive, with the team aiming to produce it for less than £500.

In April 2021, they were awarded a research grant of £1.3 million by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) to develop the device further and start intensively testing it in clinical settings, prisons and police services.

They expect the technology to be ready for use more widely within a few years.

Dr Pudney says, “I’m really proud of how we’ve worked in partnership to achieve so much in so little time. We work nimbly, fail fast and are continually learning from the process.

“This project is tackling the problem of synthetic drugs holistically – we aren’t just making a new piece of tech, but also learning how to utilise it effectively to reach the people it needs to.

“Because synthetic drugs are so difficult to detect, there’s been very little research on understanding their usage until now.

“We hope to combine this technology with a deeper understanding of the communities that use Spice so that we can deploy the spice-detecting technology in the most effective way possible to benefit the most vulnerable in society,” said Dr Pudney. “Our ultimate aim is to save both money and lives.”

Dr Oliver Sutcliffe is Senior Lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University and Director of MANDRAKE, one of the many collaborators on the project.

He says, “We have seen first-hand the devastating effects of synthetic cannabinoids on the homeless community in Greater Manchester and due to the rapidly evolving synthetic drug market, many frontline health professionals are unsure how to effectively respond to emergencies.

"Our team is extremely proud to be part of the development of this rapid field-deployable system, which offers a game-changing solution to tackling the serious drug-related harms affecting vulnerable sections of our society.”

Left to right: Dr Jenny Scott, Professor Stephen Husbands (both Department of Pharmacy & Pharmacology) and Dr Chris Pudney (Department of Biology & Biochemistry) (Credit: Nic Delves-Broughton).

Working in partnership

The team has been working in collaboration with several external partners, including police services, prisons, drug testing facilities as well as homeless and drug addiction charities.

The researchers are basing their new Spice-testing technology on a cloud-hosted data analytics platform developed by a University of Bath spin-out, BLOC Labs.

The team has partnered with Developing Health & Independence, a charity that offers a range of services for disadvantaged people in Bath & North East Somerset, Bristol, Wiltshire, South Gloucestershire and Somerset.

The team has visited HM Prison Bristol to learn more about the problems faced and how this technology could help stem the flow of drugs into these settings.

They’ve been consulting with Avon and Somerset Police, who have provided them with seized material to test, including papers and letters sent to prisoners by their families and friends.

They've also been collaborating with Bristol Drugs Project to understand the needs of users and how to help them beat their addiction.

Greater Manchester Police has given advice on developing the testing kit.

The team is also collaborating with MANchester DRug Analysis & Knowledge Exchange (MANDRAKE), one of the main testing facilities for prisons in the North West of England.

The researchers are also consulting with HM Prison Hull.

TICTAC Communications Ltd is a leading provider of drug identification and drug information to the criminal justice and healthcare sectors, based in the medical school at St. George’s University of London. They provided material for the team to test, to check the effectiveness of the device against existing qualified datasets.

The team is currently negotiating with other prisons across England and Scotland to trial the device more widely.

Working in partnership

The team has been working in collaboration with several external partners, including police, prisons, drug testing facilities as well as homeless and drug addiction charities.

The researchers are basing their new Spice-testing technology on a cloud-hosted data analytics platform developed by a University of Bath spin-out, BLOC Labs.

The team has partnered with Developing Health & Independence, a charity that offers a range of services for disadvantaged people in Bath & North East Somerset, Bristol, Wiltshire, South Gloucestershire and Somerset.

The team has visited HM Prison Bristol to learn more about the problems faced and how this technology could help stem the flow of drugs into these settings.

They’ve been consulting with Avon and Somerset Police, who have provided them with seized material to test, including papers and letters sent to prisoners by their families and friends.

They've also been collaborating with Bristol Drugs Project to understand the needs of users and how to help them beat their addiction.

Greater Manchester Police has given advice on developing the testing kit.

The team is also collaborating with MANchester DRug Analysis & Knowledge Exchange (MANDRAKE), one of the main testing facilities for prisons in the North West of England.

The researchers are also consulting with HM Prison Hull.

TICTAC Communications Ltd is a leading provider of drug identification and drug information to the criminal justice and healthcare sectors, based in the medical school at St. George’s University of London. They provided material for the team to test, to check the effectiveness of the device against existing qualified datasets.

Impact on healthcare

The impact on healthcare and drug services in the community is also potentially very significant.

“Currently you can get laboratory testing but you have to send it off and it takes several days to come back,” says Dr Scott. “In contrast, our device is a tool that could be used in an emergency setting so health professionals can quickly see whether a patient has taken Spice recently.

“They can use this alongside the patient’s other symptoms and history to make a decision around what treatment pathway to take.

“This means in some cases avoiding the need to hospitalise patients if appropriate healthcare can be given where they are.”

The device will also help drug testing in the community, so that users can test samples of Spice before they use them, to find out if they’re genuine, and to get an idea of the strength.

Dr Pudney says, “It’s not about encouraging drug use, but giving users the tools to do it in a less dangerous way so they don’t end up in A & E.

"Drugs charities have told us that when users know they can be tested at a clinic, it helps support them to get off the drugs and stay abstinent from substance abuse.”

What next?

Next, the team plans to investigate using the technology to detect other psychoactive substances such as the benzodiazepines. These are a class of sedative drugs used to help with anxiety and sleep disorders, the most well-known drug in this group being diazepam or Valium.

In the future, the group aims to start a not-for-profit social enterprise to bring their technology to the mainstream. The group plans to roll out the full range of activities necessary to deliver the technology, including portable device design, analytical software development, chemical fingerprint libraries and associated community pharmacy practice advice to deploy the technology effectively.

“We believe the scope and potential of our research is truly unique and presents the best chance for tackling Spice use in the UK and supporting the most vulnerable people in society to come off these drugs.”

Research papers

Trends in hospital presentations following analytically confirmed synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonist exposure before and after implementation of the 2016 UK Psychoactive Substances Act

Craft, S.,Dunn, M.,Vidler, D.,Officer, J.,Blagbrough, I.,Pudney, C.,Henderson, G.,Abouzeid, A.,Dargan, P. I.,Eddleston, M.,Cooper, J.,Roper, C.,Thomas, S. H. L. & Freeman, T. P.,6 Jun 2022, (E-pub ahead of print): Addiction.

Analysis of synthetic cannabinoid agonists and their degradation products after combustion in a smoking simulator

Naqi, H. A.,Pudney, C. R.,Husbands, S. M. & Blagbrough, I. S.,28 Jun 2019: Analytical Methods.11,24,p. 3101-31077 p.

Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists Detection using Fluorescence Spectral Fingerprinting

May, B.,Naqi, H.,Tipping, M.,Scott, J.,Husbands, S.,Blagbrough, I. & Pudney, C.,15 Oct 2019: Analytical Chemistry.91,20,p. 12971-129799 p.

Images by Laurie Lapworth / University of Bath, unless credited.

Video by Simon Wharf / University of Bath.