Engaging the public with the climate crisis

Extreme weather events are bringing home the realities of climate change. But what can people do in response? University of Bath research is being applied in the UK and around the world to engage the public, change behaviours and build support for ambitious climate action.

Photo by luke flynt on Unsplash

Photo by luke flynt on Unsplash

Photo by Aldward Castillo on Unsplash

Photo by Aldward Castillo on Unsplash

From ice storms in Texas to flash floods in Sudan, or forest fires engulfing Australia, Canada and Chile, extreme weather events are increasingly common around the world. Recent UK heatwaves, where temperatures topped 40°C for the first time ever, brought home a new reality that nowhere is safe from the changes caused by the effects of human-made climate change.

As widespread public realisation dawns about the climate crisis and the scale and pace of change required to decarbonise, one question looms large:

‘What difference, if any, can I make as an individual in the face of a global challenge?’

For some: not a lot. The only answer is system changes, which are reliant on those in power. For others though, that change must start somewhere. While international political and economic decisions are essential, people power also has the extraordinary potential to be transformative in responding to the climate emergency.

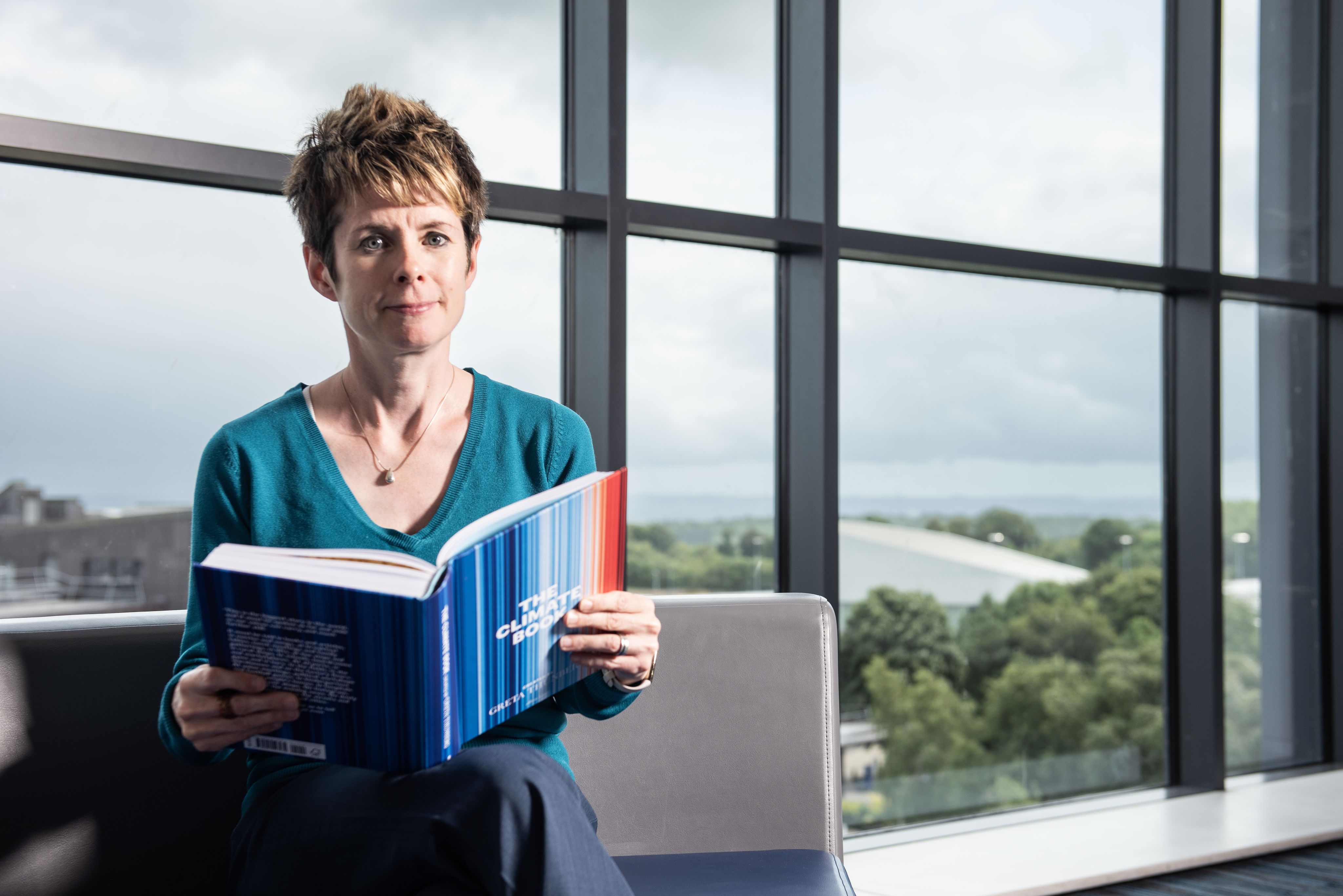

University of Bath Professor Lorraine Whitmarsh MBE is one of those people.

Lorraine is a leading international environmental psychologist, Director of the Centre for Climate Change and Social Transformations (CAST), co-Director of Bath’s Institute of Sustainability and Climate Change, IPCC lead author, government advisor and member of the Climate Crisis Advisory Group (CCAG).

For the past two decades she has been championing new approaches to engaging the public with climate change in ways which resonate, change behaviours, and build support for the policies desperately needed to cut emissions. She literally wrote the book on it.

In 2015, Lorraine edited ‘Engaging The Public with Climate Change: Behaviour Change and Communication’. Since, this has become a go-to resource for those studying and working in climate change. More recently, she co-authored a section of Greta Thunberg’s international bestseller ‘The Climate Book’. Now, as countries around the world put in place policies and actions to curb emissions, her research and expertise is in hot demand.

“Our view is that people have capacity as agents of change to bring about a low-carbon future in a variety of interlocking ways. This might be as a concerned community member acting to promote green travel, as a business leader finding ways to enable more sustainable practices, or as a citizen expressing their opinions on policy proposals and technological innovations, and, crucially, through their own individual actions.”

Unpacking the public’s role

In 2019, the UK became the first major economy to commit to achieving net zero emission reductions by 2050.

More than 140 countries have since followed suit, including some of the biggest polluters (China, the US, and the EU), legislating for significant carbon reductions within tight timeframes. In addition, over 1,000 cities, over 1,000 schools, colleges and universities, and 400 financial institutions have each joined the UN’s Race to Zero, an international campaign pledging to take rigorous and immediate actions in an attempt to halve global emissions by 2030.

To date, most emission reductions countries have achieved have been largely invisible to the public, brought about via changes to energy generation. As such they have had little impact on people’s individual lives. Reaching net zero targets will be different. The much more substantial reductions in emissions needed over the next decade to achieve carbon neutrality requires more direct public involvement as well as their sustained support, says Prof Whitmarsh.

“Whether it’s changes to the way we heat our homes, the food we eat, how or why we travel, or indeed what we buy, all of these changes will necessitate some form of public action or change,” she says. Technological fixes alone just won’t cut it.

According to the Climate Change Committee, around 60% of this next phase of emission reductions will require some amount of public behaviour change. That might be in adopting new technologies, such as electric vehicles or heat pumps, changing travel patterns, or adapting our diets to reduce red meat and dairy consumption.

Through CAST, the team regularly monitors public attitudes and perceptions about climate change, and how people think their own actions can make a difference to advise policymakers and to inform future research.

Shifting attitudes on climate change

Professor Whitmarsh’s own research interests have long revolved around people’s changing attitudes, values and behaviours in relation to climate change as well as the best ways to engage them in the topic. One of her first projects as a PhD student at Bath explored what impact the 2003 floods in the UK had on those directly affected and how this related to their thoughts about climate change.

“It seemed like a no-brainer at the time that those affected by flooding would also be the ones most concerned about the risks climate change posed, yet this wasn’t the case,” she explains. People instead interpreted flooding as being caused by more local and visible problems, such as blocked ditches and drains. In fact, people’s environmental and political values were far more likely to influence their climate change concern than any experience of extreme weather she says.

Two decades on and Prof Whitmarsh thinks values and ideology still remain the strongest predictors of people’s climate concern, but the picture is much more mixed nowadays. One of the biggest shifts she has observed has been the decline in climate scepticism and the increase in public awareness brought about through campaigns, via changing media and public discourse but also increasingly people’s own experiences of climate change effects.

“Around the world in recent years there has definitely been growing political and public acceptance that we need urgent action,” she says. “The language has changed, too. Terms like climate ‘crisis’ and ‘ecological emergency’ have become mainstream and to some extent have shifted the dial about how soon that change needs to come about.”

While climate scepticism has waned, she acknowledges that this has sometimes shifted to climate ‘delayism’ among those who argue that the financial cost of climate action is too great given other pressures. More broadly, she says that although people are aware of the problem and want action to be taken, there is generally less clarity on where attention should be focused and how changes can be brought about.

This is where CAST’s expertise is making significant inroads.

Through CAST, Prof Whitmarsh and colleagues focus on four challenging areas which have the potential for substantial climate impacts, but which have so far proven difficult to change.

These cover: transport and mobility, heating and cooling, food and diet and material consumption.

Against these priorities, their research programme is structured around four themes: ‘Visioning’; ‘Learning’; ‘Trialling’ and ‘Engaging’.

Listen to Professor Whitmarsh on the Research With Impact podcast

Planes, trains, automobiles and other areas of behaviour change

Driving

About 15% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions come from cars and the number of miles driven is still increasing year-on-year.

Government advice is that all new cars and vans should be electric in 2030 or soon after. In May 2024, despite a substantial increase in sales only 17.6% of all new car registrations were electric vehicles (EVs).

Supported by the University’s Policy Fund, CAST has conducted research with Scottish Government helping to create a toolkit for how people can reduce their car use.

Photo by Victoria Prymak on Unsplash

Photo by Victoria Prymak on Unsplash

Active and public travel

Walking, cycling, or taking public transport is perceived as a very effective climate change response in reducing car use. With over half of all journeys made under 5 miles, greener travel has the potential to substantially reduce emissions.

CAST has been working with Cornwall Council to test an e-bike intervention with households.

Previously the team worked with staff at the Council to reduce business miles and EV use.

Photo by Gary Lopater on Unsplash

Photo by Gary Lopater on Unsplash

Flying

As a proportion of national emissions, flying has so far been relatively small. However, for those who do fly, aviation is likely to represent a significant part of their carbon footprint. While other sectors are set to see their emissions reduce over time, aviation is projected to grow substantially. By 2050, it may account for as much as a third of the UK’s overall emissions.

With the charity ‘Possible’, CAST are currently examining workplace initiatives designed to reduce air travel. Previous analysis from CAST for Ipsos MORI for its ‘Net Zero Living’ report in 2022 identified the highest levels of public support in response to net zero was the introduction of frequent flyer levies.

Photo by alpha innotec on Unsplash

Photo by alpha innotec on Unsplash

Cooling and heating

Many houses across the UK are not well-insulated, meaning that power generated to heat homes is being wasted, and most are heated by gas boilers.

We urgently need to improve energy efficiency and to convert home heating systems to heat pumps or hydrogen systems. Additionally, as temperatures increase, it is expected that energy demand for cooling systems (air conditioning) will significantly increase.

Current CAST research is investigating how and whether people are investing in low-carbon cooling options.

Food choices and food waste

A quarter of our emissions come from the food we eat, but this can vary a lot depending on a person’s diet. Limiting beef, lamb and dairy products can substantially reduce the climate impact of food. Lowering food waste is also important for bringing down emissions.

To promote low-carbon dietary changes, CAST has tested a new model of producing food, called community-supported agriculture (CSA) which found wellbeing benefits for individuals as well as a lower carbon footprint when people consumed local food. Learn more about the research.

Its other research has tested how environmental versus health messaging encourages less red meat consumption.

Prof Whitmarsh also coordinates a student-led Vertically Integrated Project on sustainable food which has tested various initiatives to promote plant-based food on campus.

Photo by Jezael Melgoza on Unsplash

Photo by Jezael Melgoza on Unsplash

Shopping

Major environmental impacts arise from the materials and products we buy. Some direct consequences are well-known, such as the problems of plastics in the oceans. But there are also climate change impacts arising from the extraction, processing, transportation, use and discarding of a much wider range of materials.

Analysis from CAST looking at the individual-level effects of taking environmental actions shows that people’s wellbeing increases when they reduce consumption.

Old habits die hard

For a long time, environmental campaigners had been working on an assumption that behaviour change in relation to these environmental challenges could be achieved by explaining the problem to the public: the more information and evidence you could give people about the problem, the more likely you would raise their awareness, and changes to their behaviour would flow from this.

This form of one-way communications became dominant in the 1990s and 2000s: from government communications to campaigning materials and documentary films, such as Al Gore’s famous 2006 documentary ‘An Inconvenient Truth’.

Whilst Professor Whitmarsh says this has been important for raising awareness of the issue and building public support, the ‘tell them and they’ll change’ approach has more often failed in bringing about widespread actions required. Her analysis suggests that one-way, linear, broadcast communications can fuel a ‘value-action gap’, whereby the public is aware of the problem, but face psychological barriers to understanding their own role within it and the behavioural and structural challenges to action.

Alongside University of Bath Emeritus Professor Bas Verplanken, a leading author on the science of habits and the concept of habit discontinuity, Prof Whitmarsh has pioneered new, more sophisticated approaches to achieving behaviour change by targeting interventions at so-called ‘moments of change’ in people’s lives.

Professor Bas Verplanken

Professor Bas Verplanken

These include major lifestyle upheavals like moving house, getting married or having a baby, starting a new job, or even adjusting to major global events such as Covid-19. During these moments, people are typically more open and receptive to changes and by adopting new behaviours adjustments are more likely to stick, she says.

The team has advised local authorities and large organisations on using this approach to great effect. They have shown how so many of our everyday actions, like commuting, are performed on autopilot and that we can use moments of flux to reprogramme what we do, whether that’s cycling instead of driving to work or having a ‘Meat Free Monday’. However, she warns the window of opportunity to change habits only stays open so long: go past a few months and habits are locked in again.

A number of these insights into behaviour change fed into the 2022 House of Lords Environment and Climate Change Committee report ‘In our hands: behaviour change for climate and environmental goals’. Prof Whitmarsh was the inquiry’s special advisor, while her co-author on a number of behaviour change studies and CAST Associate Director Professor Wouter Poortinga (based at Cardiff University) provided evidence.

The report calls on the government to learn from examples of where it enabled behaviour change, including during the pandemic, and to enable people to make the necessary shifts in how we travel, what we eat and buy and how we use energy at home. It suggests that government needs to use every lever – regulations, financial incentives and disincentives, changes to infrastructure, and education – to address the barriers which currently prevent people from changing behaviours across key areas.

Most importantly, however, it highlights the importance of putting fairness at the heart of behaviour change interventions to avoid placing a burden on those who can least afford it. One example of this is providing financial support for low-income households as part of a national drive to improve the energy efficiency of our homes. Prof Whitmarsh says this is a crucial piece of the jigsaw. “The importance of fairness is shown so consistently from all research on public acceptability of policies, not just climate policies. People often care more about “is it fair?” than “does it work? It’s fundamental to get this right,” she says.

“People power is critical to reach our environmental goals, but unless we are encouraged and enabled to change behaviours in how we travel, what we eat and buy and how we heat our homes, we won’t meet those targets. Polling shows the public is ready for leadership from the government. People want to know how to play their part in tackling climate change and environmental damage."

Baroness Parminter

Baroness Parminter

The House of Lords report also calls for the launch of a public engagement strategy to build support for net zero and to help people adopt new technologies and reduce carbon-intensive consumption in key areas where behaviour change is required. Prof Whitmarsh says one of the lessons from the pandemic is how crucial clear communication is in building public understanding and consensus around climate actions.

Her research has also looked at ways to build deeper levels of public engagement on the subject.

Fostering deeper engagement

Over recent years, there have been a proliferation of climate assemblies, citizens panels or juries taking place both in the UK and internationally built on a model of deliberative or participatory democracy. Campaigning organisations like Extinction Rebellion (XR) have long argued that we need citizens assemblies to spur the societal changes required. It’s a strong argument and the model is gaining lots of traction, thinks Prof Whitmarsh.

Like a jury in a criminal trial, these forms of engagement work by bringing together a sample of the public to listen to evidence, debate, discuss and come to collective conclusions about the best way ahead. They are held up as a useful approach where no settled point of view exists, where complex trade-offs are involved, or where the issues debated are controversial. In a different context, one of the most famous examples in recent years was Ireland’s Citizens Assembly on abortion which brought about landmark changes.

Prof Whitmarsh has seen first-hand the impact these forums can have on individuals’ own beliefs and actions when it comes to climate. Having advised various local authorities across the UK on implementing deliberative exercises, she was an expert lead for the UK’s ‘Climate Assembly’ (CAUK) in 2020 when, for the first time in its history, Parliament decided to put the question of how we reach our national climate targets to the people through a UK-wide climate assembly, which involved 108 people from across the UK.

Following their deliberations, CAUK produced a report to Parliament ‘The Path to Net Zero’. This sent a clear message back to lawmakers that the public supported bold climate action to deliver Net Zero by 2050 but that net zero policies needed to be fair and backed by better public awareness, choice, and clear leadership. CAUK’s report was forwarded to Number 10 and welcomed by government ministers. It was also used as evidence by the Climate Change Committee for their Sixth Carbon Budget which, in turn, informed the government’s pledge to cut national carbon emissions by 78% by 2035.

Meet Sue

One of those 108 CAUK members was Bath resident Sue Peachey. A self-confessed non-expert on climate change before taking part, she has since gone on to make numerous changes in her life to be more environmentally-friendly, including buying an electric car. She also became a Parish Councillor and through her actions and campaigns is encouraging others locally to wake up to the challenge and act.

“After several months of us all listening to advocates and experts, we reached the conclusion that change is imperative and set out our practical recommendations to make that change happen in a way we hope most people would find acceptable and achievable.”

Sue was part of a delegation which presented the report’s findings in Parliament along with Sir David Attenborough. She was also the star of a prime-time BBC documentary ‘The People Vs Climate Change’, which highlighted the Citizens’ Assembly and the inspiring stories of those involved.

Professor Whitmarsh says that Sue and many of the others involved in CAUK demonstrate how and why citizens’ assemblies can be transformative in terms of people’s beliefs and actions. However, she acknowledges Climate UK could have had more impact within government.

An equivalent citizens’ assembly which took place in France around the same time – ‘Le Convention Citoyenne pour le Climat’ – was instigated by President Macron, unlike the UK version which was led by Parliament. Macron promised to respond to that report and since various recommendations have been taken forward, notably France’s decision to ban internal flights.

“That level of government support for future citizens’ assemblies could be a real game-changer in the UK,” says Prof Whitmarsh.

CAST analysis of citizens’ climate assemblies, analysing the deliberations and wider process, has highlighted these effects. This is now feeding through to its latest work with the EU Knowledge Network on Climate Assemblies (KNOCA), led by Deputy Director Dr Christina Demski, evaluating the impacts of the French and Spanish assemblies.

The CAST team has also advised the Scottish, Welsh, and Northern Irish governments on deepening engagement with the public. This included providing advice to the Scottish government on its 2021 Net Zero Nation: Public Engagement Strategy – the first government public engagement strategy on net zero in the world. They were also commissioned by the Climate Change Committee to review the evidence on behaviour change and public engagement, informing their seventh carbon budget for the UK government.

Internationally, in 2021, Prof Whitmarsh joined the Climate Crisis Advisory Group (CCAG) – the prominent, international, and independent body of experts, led by former Government Chief Scientific Advisor, Sir David King, advising policymakers on the climate crisis and net-zero transition. The group is working with C40 – the global network of mayors of the world’s leading cities and has held high-level events at COP.

Through the ActNow project, being coordinated by the University’s IPR, Prof Whitmarsh was also one of several high-profile climate experts to be featured at COP28.

Staying positive

Amid increasingly dire warnings from the IPCC and others about the risks posed by climate change, Prof Whitmarsh is often asked how to remain optimistic. She describes actions to cut carbon emissions as a race against time and the very clear threats that climate change poses.

“Things are moving so quickly in relation to climate change, and it is clear we do not have endless time left to act. But there is still a window of opportunity, and my passion is to keep pushing at this, so that we can do all we can to protect the planet for future generations to enjoy,” she says.

Some of the CAST team’s latest research has explored rising incidence of eco-anxiety among young people. Ground-breaking research at Bath led by Caroline Hickman and Dr Liz Marks released in 2021 to worldwide attention showed that nearly half of young people were affected by eco-anxiety caused by governmental inaction to tackle climate change. Prof Whitmarsh and colleagues have developed this further and found that eco-anxiety can actually be a driver for positive change.

Finally, there’s a message from CAST about modelling the changes you want to see in others when it comes to the environment and how taking such actions can be both motivating and positive for individual wellbeing. Prof Whitmarsh’s research has looked at the wider benefits to taking pro-environmental actions, such as the health and wellbeing benefits of changing diets or increasing active travel.

“Sometimes behaviour change in relation to climate is presented as a limiter, that we are being prevented from doing something. Our research has shown how very many of these changes can be enabling and beneficial to people’s lives: they report feeling happier and healthier as a result. The more we will shift social norms and help bring about the shifts in society which are so important right now,” she says.

Learn more about our Research With Impact

Culturing meat for sustainable nutrition

Growing meat instead of rearing animals to eat could radically change our diets. At Bath, we're leading on making it work at scale.

Developing a sustainable alternative to palm oil

How a yeast fed on waste could take a seat at the dinner table – and curb deforestation

Powering up the UK's energy transition

A University of Bath team is leading the charge toward reform in the energy industry, cutting carbon emissions and costs by blending cutting-edge digital technologies, artificial intelligence and economic policy innovations into globally influential research.